By Su Lin Lewis, Lecturer in Modern Global History.

How do you start the story of a city? The Hong Kong Museum of History begins in the volcanoes and oceans that converge to form a rocky, lush island, and the folk traditions of small fishing communities and pearl divers. At the start of the next section of the museum, visitors are confronted with the imposing, bronze statue of Lin Zexu, China’s imperial commissioner who, in 1839, ordered the destruction of 1.2million pounds of opium in Canton and wrote an open letter to Queen Victoria to stop the poisoning the Chinese people.

© Su Lin Lewis

This opium trade is also the historic backdrop of Amitav Ghosh’s latest novel, Flood of Fire. The book is the final instalment of a trilogy that begins in the poppy fields of Bengal, tracking an eclectic cast of characters – a mulatto ship’s mate from Baltimore, a Parsee trader, a disgraced raja, a Chinese opium-addict – across the Indian Ocean. They travel from Calcutta to a penal colony in Mauritius, then to Canton, and, in the third volume, back to Calcutta and the China coast amidst the First Opium War, which eventually ended in the cession of a sparsely populated Hong Kong island. Ghosh’s immaculately researched novels remind us that we cannot view Hong Kong’s history in isolation, but as part of a dynamic story of nineteenth-century trade, mobility, and power in maritime Asia.

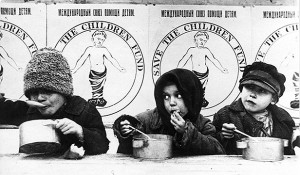

Modern Hong Kong was a city born out of an insatiable demand by British traders for Chinese goods. Apart from New World silver, opium, much of it grown in British India and exported to China in the early 1800s, was one of the few items that Chinese would buy from Europeans. When Chinese officials cracked down on opium imports, Britain responded with a call for war.

From its seizure in 1842, Hong Kong exploded as a trading emporium, not only for opium but for imports of Indian cotton, wool, and metals, and exports of Chinese tea, silk, and porcelain. Throughout the nineteenth century, thousands of Chinese, as well as Europeans, Portuguese, Indians, and Malays flocked to the city for work and opportunity. For Chinese ‘coolies’, Hong Kong became a key port of embarkation to work in the gold mines of America and Australia.

Hong Kong’s history is thus profoundly global, both in its origins and in its rich, modern social and economic history, crosscut with the movements of migrants and openness to foreign trade. I was recently in Hong Kong for the launch of the Hong Kong history project, a collaboration between the University of Bristol and the University of Hong Kong, and other partners, to examine new avenues of research into Hong Kong’s history, situating the city within Chinese, imperial, and global history.

The workshop unravelled the multiple layers of the city’s history, from the hidden histories of colonial Hong Kong’s cosmopolitan communities, such as the Eurasians, to its lineage of social movements, from the 1967 riots, where activists and trade unionists staged a mass protest against British rule, up to last year’s umbrella revolution. We heard of untapped sources, like the Japanese archives, and fascinating oral history projects with Hong Kong’s boat people, encouraging us to view the city from the water, rather than the land.

My own contribution, as an interloper, was to frame Hong Kong as a node within global, cosmopolitan social networks that spanned maritime Asia, from Bombay to Shanghai. In Hong Kong, I encountered the same mobile trading communities that populate Ghosh’s novels, and that I was familiar with in my own research on colonial port-cities in Southeast Asia: Chinese, Armenians, Baghdadi Jews, and Parsees, who followed the networks of empire, and played a major role in shaping the urban environment of its port-cities, investing heavily in industries, transport systems, hotels, and steamships.

There are other, illuminating connections between Hong Kong and Southeast Asian in the colonial era. In the early nineteenth century, missionaries were expelled from Canton by imperial decree; they moved their press to Malacca, which became the home of the first Chinese periodical press, the Chinese Monthly Magazine, and then back to Hong Kong in the 1840s. In the 1920s and 1930s, revolutionary press networks connected Hong Kong with Southeast Asia, as Sun Yat-Sen’s supporters funded multiple press ventures, in English, Thai, and Chinese, throughout Malaya, Siam, and Burma. Groups of Chinese, Indian, and Malay students from Penang and Singapore went to Hong Kong’s University (founded in 1911) for higher education. The Shaw brothers, cinema pioneers of 1930s Asia, set up studios in Singapore, Shanghai, and Hong Kong.

Unlike Rangoon and Penang, the cities where I’ve spent most of my research, the built environment of Hong Kong doesn’t immediately exude a sense of its colonial past. Much of the city’s old architecture was destroyed to make way for high-rise buildings on an island where living space is at a premium (land reclamation efforts have been happening here since the 1850s). What few colonial-era buildings are left are tucked away downtown in small, leafy oases (like the St. John’s cathedral) or dwarfed, like the neo-classical High Court building, by skyscrapers and ultra-modern architecture, including Norman Foster’s HSBC building. The Peak, once an area where Europeans built palatial residences to escape from the warm, humid climate of the city, is now a popular, shiny shopping and recreational complex. though you can still travel there by tram.

Hong Kong is undoubtedly a modern Asian city, but one also prominently at the edge of the Pacific Ocean. Its hilly, buzzing downtown core is reminiscent of San Francisco’s Market Street and especially Chinatown, with its historic links to Hong Kong and the southern China coast. There are many stories and routes we could take in telling the story of this very global city, where, under its gleaming, modern face, the past persists in subtle ways.