Today, 17 December 2020, marks the eighty-fifth anniversary of the first award of a PhD by the University of Bristol to a Chinese student, Yu Jianzhang. Yu received his award from Vice-Chancellor Thomas Loveday in a ceremony in the Great Hall. As part of the ‘100 Years of PGR’ project, being co-ordinated by the University’s Bristol Doctoral College, supported by the Brigstow Institute and our John Reeks, a team including two historians has been developing a bank of material about the history of PhD study at Bristol. Following on from our earlier story about the first Chinese undergraduate at Bristol, current history PhD student Liu Xiao — who is working on the history of science in China — has built on their work, and on materials provided by colleagues at Jilin University, to pen this introduction to Yu Jianzhang’s life and career. Continue reading

Category Archives: University history

Looking for Chan Ching Yau: the first Chinese undergraduate at Bristol

Chan Ching Yau: The first Chinese undergraduate at the University of Bristol

‘In passing’, a colleague in our Library Special Collections recently wrote in an email to me, ‘I saw the attached entry in the ‘Register of Undergraduates’. ‘Passing’ being relative, he appended the file reference number and all the details: Chan Ching Yau, of 3170 Great Western Road, Shanghai (date of birth: 21 August 1897; matriculated: 27 November 1916).[1] Mr Yau’s entry was no 1,027. ‘I wonder what happened to him?’, he signed off, provocatively.

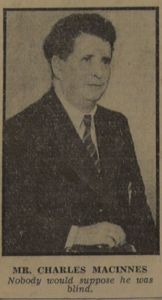

Professor Charles M. MacInnes: The University of Bristol’s Blind War Hero

In the wake of Canada Day, Dr John Reeks looks at the war work of Canadian-born University of Bristol historian Charles M. Macinnes.

Charles M. MacInnes, known to his friends as ‘Mac’, joined the University of Bristol in 1919 as Assistant Lecturer in History. A Canadian by birth, and despite being nearly completely blind, he rose quickly through the academic ranks. In 1922, he was awarded £20 for research into the history of the tobacco trade and thereafter started to take on a number of research students in the fields of colonial history, the history of slavery, and British political history. He published widely on these subjects, including his first book, The Early English Tobacco Trade, published in 1926, and his 1934 England and Slavery, which made the case that ‘much remains to be done’ to eradicate the evil practice from human society. Following the death of Professor Robert B. Mowat in a plane crash in 1941, MacInnes was promoted first to a readership and then to the professoriate, subsequently becoming Head of History in 1943, before finally rising to take the Deanship of the Faculty of Arts in 1952.

In retirement, MacInnes wrote several more books but one is particularly notable: 1962’s Bristol at War, an account of the city’s reaction to, and suffering during, the Second World War. It is, by professional standards, a failure. MacInnes was clear at the outset that he wanted to avoid writing a book aimed at scholars, or in other words, ‘a trickle of text running through vast meadows of footnotes’. This he certainly achieved. Bristol at War is both readable and instructive, informing the reader about the vast civic undertaking that constituted Bristol’s war effort, whether that be the work of the Women’s Voluntary Service in training ambulance drivers and receiving troops evacuated from Dunkirk, or the Lord Mayor’s War Services Council, which raised and expended nearly £100,000 for a variety of wartime causes between 1940 and 1945. The book in nonetheless nothing short of being a whitewash. One crucial individual is consistently and deliberately written out of Bristol’s wartime history, a person who had won widespread plaudits for his labours at the time and had even been awarded a CBE for his efforts in the 1959 New Year’s Honours. That figure was MacInnes himself.

Bristol Archives hold sixteen large folders of letters and documents which MacInnes had collected in the process of compiling materials for Bristol at War. Organised thematically – ‘Anglo-American Relations’, ‘The Lord Mayor’s War Service Council’, ‘Bristol Information Committee’, and so on – they closely parallel the chapters of the book itself. Upon opening the files, though, it becomes quickly apparent that many of these letters are coming into and going out of MacInnes’s own offices at the University: despite not awarding himself a single mention in Bristol at War, not even the briefest of footnotes, MacInnes himself was at the very heart of Bristol civil wartime operations. I shall take just three examples of his involvement, though there are many more.

First, he was a member of the Bristol Information Committee and convened a subcommittee tasked with improving civilian attitudes to the evacuation of children during the Blitz. During the so-called ‘Phoney War’ of summer 1940 the problem of children returning to the dangerous city caused a great deal of anxiety among Bristol’s political leaders. In a letter of 3 March 1941 to Phyllis Forbes-Dennis, who was seeking to draw inspiration for her own campaign in Plymouth, he explained that ‘it has been my function to disseminate information by means of loud-speaker vans for various authorities’. He went on to explain that his present preoccupation was drawing up a report on morale in Bristol, which could be used to inform the decisions then being made. The subsequent report found its admirers on Bristol’s Council, in the offices of the Regional Information Committee, and the Ministry of Health. Not content with academic investigation, he took practical steps, including organizing twenty Christmas parties – for thousands of Bristol’s citizens – in the winter of 1940. MacInnes also saw to it that ‘travelling troops of players and entertainers…will be visiting bombed areas’ in an effort to boost morale. These parties and entertainments were extremely successful. On 13 August 1943, H. V. Hindle, Secretary to the Lord Mayor’s War Services Councils, wrote to MacInnes to explain that despite cutting back on ‘air raid recuperative work’, the committee ‘strongly felt that the Christmas parties for old people and children should still go on’.

Second, he was at the fore of efforts to improve understanding and to promote friendship between the people of Bristol and the citizens of Allied nations, many of whom, especially the Americans, were now stationed in Bristol itself. One such initiative was the organization of lecture tours, in collaboration with civic organisations like the Rotary Club and the main political parties. ‘The object of these lectures’, MacInnes explained in a circular dated 29 June 1940, was to ‘strengthen the morale of the civil population’ and to promote ‘the feeling of confidence as to the issue of the war’. As the years rolled on, the lectures increasingly focused on the contributions of Britain’s allies and speakers encouraged Bristol’s citizens to return the kindnesses that had been shown to them in the dark days of the Blitz. MacInnes was a person to whom Bristol’s great and good would always answer the call. When he convened an unofficial meeting at the University in February 1943 to discuss the deteriorating relationship between the city and American merchant seamen stationed there, representatives from the Bristol Port Authority, the W. V. S., the Ministry of Information, and the American Red Cross were all in attendance. He was also not above writing speculative letters to foreign ambassadors and consuls, in the hopes of procuring useful materials for his activities. In a 1943 letter to Canada House, for instance, he suggested putting on so-called ‘Canada Parties’ in Bristol: ‘it would be nice if…the Canadian touch could be in evidence’.

Third, he capitalised on his academic connections to organise recuperative holidays in Oxford for heavily-overworked and war-fatigued Bristolians during the autumn of 1941, particularly those living in dangerous parts of the city. In all, approximately 7,000 citizens took advantage of the scheme, which saw them placed in Oxford colleges for a two-week period. There, they could sight-see, play a game of cricket, or merely relax in a park or quad. So successful was the ‘Holidays in Oxford’ scheme that it made the national press, with the Daily Express reporting on 13 July 1941 that Bristol’s ‘soldiers of the Home Front…are being led into peace’ by Charles M. MacInnes, a ‘jolly, red-faced man of nearly 50, with blue eyes, shaggy hair, and tons of determination’. In all, the scheme cost nearly £20,000, though some colleges like Oriel were so happy to help that they refused to charge a penny. In MacInnes’s own words to the President of Magdalen in a letter of October 1941, the scheme ‘will help substantially to maintain public morale no matter what disasters may befall us…Bristol will always be grateful to Oxford for what it has done’. Similarly, one might add, Bristol owes a debt of gratitude to ‘Mac’ himself, without whom none of this would have been possible!

Yet, when he came to write his memories up in Bristol at War, MacInnes systematically removed himself from the story. Christmas parties had been organised ‘by the aid of the Lord Mayor’s grants’; the success of the Oxford holidays was simply attributed to the fact that ‘Bristol’s connection with that University in the past had at times been intimate’. The Lord Mayor gets the credit for tirelessly ‘reminding American friends that men from the old city on the Avon were the first Britons ever to set foot in the New World’. Even the ubiquitous loudspeaker vans appear from nowhere, and are simply described as having been ‘at the disposal [of the Ministry of Information]…manned by voluntary drivers and broadcasters’. Quite why he did this is unclear: perhaps through scholarly reluctance to write about himself, or perhaps because he was possessed of an almost super-human humility.

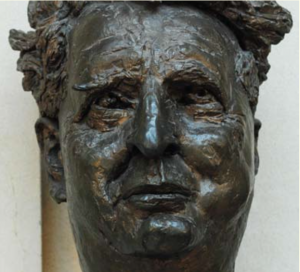

Picture 2: Bronze Bust of MacInnes by Jacob Epstein, Bristol City Art Gallery. No known copyright restrictions.

The upshot is that MacInnes is remembered in the documents but not the history. The evidence of his involvement in the civic war effort is everywhere in the archives, but nowhere in the books and articles. A profile in the University of Bristol’s centenary edition of the alumni magazine Nonesuch ironically mentions the fact that MacInnes was ‘well-known for his Christmas parties’ without passing comment on the many thousands of ordinary citizens who benefitted from them during Britain’s ‘darkest hour’. It carries a photograph of the 1957 bronze bust of MacInnes produced by Jacob Epstein without questioning why the pioneer of modern sculpture would be commissioned to honour a mere Professor of History. The blame for these omissions ultimately lies with MacInnes himself. Perhaps the truth is that ‘Mac’ was uniquely ill-placed to write the history of Bristol at war: too close to events, too intimately involved, and too modest, to write an honest account of what transpired. His braille typewriter, which had such a good war in Mac’s hands, was employed in his retirement to write an incomplete and ultimately highly misleading piece of history. ‘Bristol at War’ still awaits its historian: so too does Charles MacInnes.

The following sources have been consulted:

Charles M. MacInnes, Bristol at War (Museum Press: London, 1962)

Bristol University Library, Special Collections, Faculty of Arts Minute Books, DM2287/3/4

Bristol Archives, Papers of Professor Charles M MacInnes, 11757/1-16

Nonesuch, Spring 2009, Issue 2

South Asian Migrants and Bristol

Our new colleague Dr Sumita Mukherjee looks at the place of Bristol city and university in the modern history of South Asian migration:

David Olusoga’s BBC2 programme Black and British: A Forgotten History has brilliantly demonstrated the ways in which peoples of African descent have been living in Britain since the Roman times, how they have been part of the fabric of British life and society for centuries, how migration and multiculturalism are not twentieth-century phenomena.

It should go without saying that just as men and women of African descent have lived and played their part in British history for centuries, so have men and women from Asia, including men and women from the Indian subcontinent. Much of my research has focused on Indian men and women who came to Britain in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, before the more large-scale migrations of the post-war era.

A study of the effects of such migrations could focus on the city of Bristol. Bristol has many long-standing connections with Indian men and women. These links are publicly noted in College Green with the statue of Indian reformer Rammohan Roy. He came to Britain in 1831, was present at King William IV’s coronation, and politicians and philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham, Thomas Macaulay and Robert Owen all clamoured to meet with him. He was a vocal champion of women’s rights, and human rights more broadly.

Rammohan Roy statue at College Green, Bristol. Original image & CC licence here.

In 1833, staying in Bristol with Minister Lant Carpenter and his daughter, Mary, Roy died of suspected meningitis. He was buried in Bristol. A few years later, Dwarkanath Tagore, the father of Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore, shifted Roy’s grave to Arnos Vale and erected a monument; Roy’s tomb at Arnos Vale Cemetery is grade 2 listed, a tourist attraction and remains a site of commemoration for members of the Brahmo Samaj, the reformist group he founded.

Image of Rammohan Roy tomb at Arnos Vale (author’s own image).

Mary Carpenter moved to Red Lodge after the death of Roy, and it was there that she hosted, Keshub Chunder Sen, another Brahmo Samaj reformer, on his tour of England in 1870. Carpenter tried to make Sen comfortable by preparing ‘curry and rice’ for him in her Elizabethan drawing room, and together they formed the ‘National Indian Association’, first in Bristol (September 1870) and then in London (1871), as a place for Indian visitors to meet like-minded British people and to discuss reform issues.

Bristol was eulogised by many Brahmo Samajists and so Mary Carpenter hosted many other Indian visitors in the nineteenth century who came to pay their respects at Roy’s grave, and to build networks among like-minded reformers. They include Sasipada Banerji, whose son was born on 10 October 1871 at Carpenter’s house and named Albion, after his birth place. The family returned to India in 1872, but Albion came back later to Britain to study at Oxford.

Indeed, in the early twentieth century, the largest foreign student body at British universities were Indian students. Many Indians were encouraged to visit Britain to pursue higher education, having been educated in institutions in India that were modelled on British schools and colleges. In the academic year 1930-1, Bristol University had 28 Indian students. As John Reeks has discovered, one of those students, Man Mohan Singh, attempted to be the first Indian to fly from England to India in 1930. He was unsuccessful.

Another noteworthy example is Sukhsagar Datta, who came to Britain in 1908. He married Ruby Young in 1911, and joined the University of Bristol Medical School in 1914, qualifying as a doctor in 1920. He first worked at the Bristol General Hospital, and eventually the Stapleton Institution (now called Manor Park Hospital) until his retirement in 1956. Datta joined the Labour Party in 1926 and became chair of Bristol North Labour Party in 1946.

Bristol continued to host, and became home, for many more men and women of Indian origin. Many of these stories have yet to be uncovered; their names are hidden in censuses, their faces obscured in photos. Their stories are interwoven with other migrant groups, and together they have shaped the architecture and history of Bristol and Britain.

Remembering George Hare Leonard, 1863-1941

An institution is comprised of more than just buildings, hierarchies or symbols. When the University of Bristol was founded in 1909, its managers and patrons rushed to explain its purpose in terms of what it stood for: a common culture – an attitude – of excellence, improvement, and civic responsibility. But these are just fine words until they are given meaning by real people actually enacting these values, promoting and defending them.

Today – graduation day – is a very important day for University of Bristol historians. One of the ways we celebrate our students’ success is through the award of prizes for high attainment. The George Hare Leonard Prize is awarded to the graduate with the best overall performance, but who was George Hare Leonard, and what does the fact that we attach his name to such a prestigious award mean?

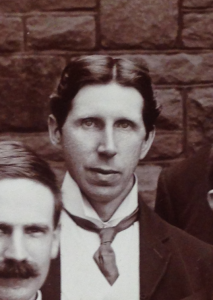

Born in Clifton, Leonard took his BA and MA in History at Cambridge, returning to Bristol to deliver the Cambridge Extension Lectures in the 1880s and 1890s. He was eventually appointed Lecturer in History at University College Bristol in 1901, rising to the rank of Professor in 1905. Only one one other candidate was interviewed for the professorial job: Frederick Maurice Powicke, who would go on to rise to the very top of his discipline by becoming Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford.

But Leonard was something special, and everybody at University College knew it. The College’s great patron, John Percival, the Bishop of Hereford, remarked in 1908 on the ‘good work’ that he and ‘the younger teachers’ were doing there. This stood in contrast, Percival claimed, to ‘older professors’ who had ‘lost touch with the working classes’. Leonard’s retention as professor came at just the right time to make a real impact, for in 1909 the College became the University of Bristol. At this institution Leonard stayed until his death in 1941.

There is much to celebrate about Leonard’s life, and his contribution to our institution, our discipline, and our city. Four highlights may serve to underline why he is worth remembering.

First, he used his professorship to reinvigorate the intellectual quality of historical studies at the College by introducing a new syllabus in the 1906/07 academic year. For the first time ever at Bristol, students were expected to become acquainted with primary sources directly, and to engage in a dialogue with their lecturers. Out went grand lecture series which tried to locate the greatness of the English psyche in the misty forests of fifth-century Saxony; in came the latest historiography, original documents, and a spirit of common intellectual purpose. These are the principles which still form the core of the degree at Bristol today, where our students are encouraged to form their own opinions, and to share and defend them in rigorous but collegiate seminars.

Second, he held a firm belief that the production of historical knowledge was an endeavor of real value, arguing that history ‘cast light on modern problems which engross the attention of all thoughtful men’. We encourage all our students to consider the purpose of what we all do and, whether we agree with Leonard or not, the willingness to engage in critical self-reflection is an important skill which we try to encourage all at Bristol to adopt. Above all we want our graduates to be self-confident in the value both of their discipline and of their own beliefs and ideas.

Third, he was strongly committed to the equality of all persons. While holding his professorship, he headed up a committee and acted as fundraiser-in-chief for the erection of a memorial to Mary Clifford, a nineteenth-century campaigner for women’s welfare, in Bristol Cathedral. This was neither an easy nor a meaningless gesture: in the 1910s, attacks on Suffragette headquarters in Bristol were widely reported in the national press. Leonard was a person willing to speak out, but perhaps more importantly, to put his ideas into action.

Fourth, he ‘gave himself heart and soul to the cause of adult education’, according to the writer of his obituary in The Times. This was an accurate assessment. Not only did Leonard frequently hold the management of the University to account on the issue of ‘educating the working men and women’ of Bristol, but he also gave up what little time he had spare to read their poetry, respond to their letters, or even go rambling with them – even if they were not registered students. At Bristol today, we celebrate continuing education and aspire to widen access as far as possible, because we see that education can have a transformative impact on peoples’ lives.

So, when we award the George Hare Leonard Prize today, we do more than just remember one of our department’s ancestors. We celebrate a great historian, certainly, but we also recognize a set of timeless values which bind us together – staff, students, and graduates alike. We celebrate both individual excellence and a collegiate spirit, the importance of rigour, but also the enduring value of historical thinking. In offering an award in Leonard’s name, we look not a committee to define our values for us, but to our own past.

Special thanks to colleagues in the University of Bristol’s Special Collections, who helped to identify some of the sources which form the basis of this judgment: Leonard’s own correspondence, that of the Bishop of Hereford, Calendars of the University College Bristol, and various newspaper cuttings.

Dr John Reeks, Teaching Fellow in History.

Bristol University to the Somme

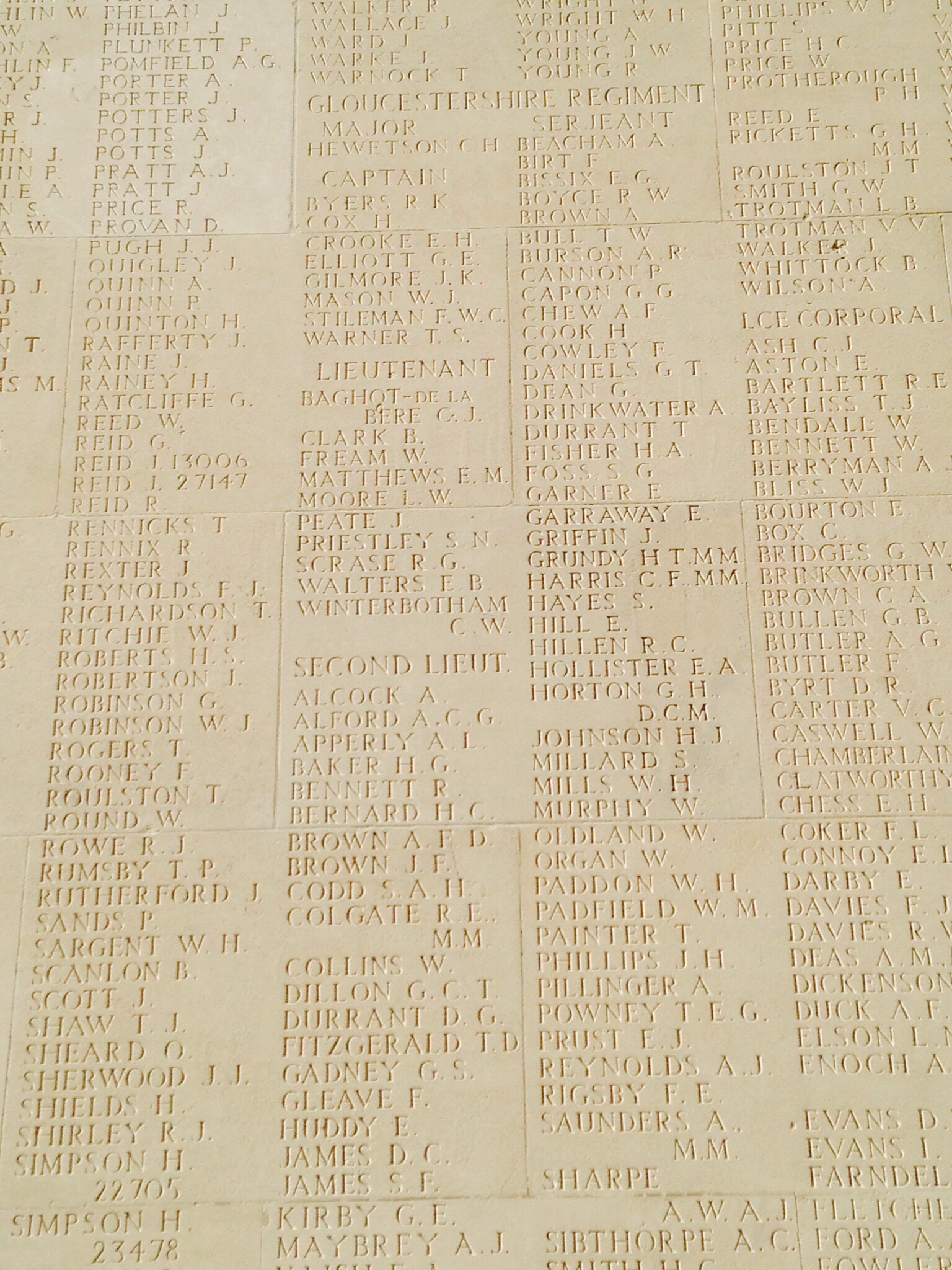

There are 173 names recorded on the University of Bristol’s memorial to those who died in the First World War. Captain W. J. Mason is one of these. A Lecturer in Economics, and head of the department, William John Mason was killed 100 years ago today, at La Boisselle on the Somme. He was 27.

There are 173 names recorded on the University of Bristol’s memorial to those who died in the First World War. Captain W. J. Mason is one of these. A Lecturer in Economics, and head of the department, William John Mason was killed 100 years ago today, at La Boisselle on the Somme. He was 27.

An LSE graduate, Will Mason was appointed to his post at Bristol in early 1914, and his role also included delivering lectures for the Workers’ Education Association at the recently-established University Settlement in Barton Hill. Mason joined the University’s Officer Training Corps at the outbreak of the war, was gazetted to the Gloucester Regiment in November 1914, arriving in France in July 1915. In January the following year he was promoted to Captain, serving with the 8th Gloucesters. Some 32 members of the university’s teaching staff were on active service by the time he was killed. An earlier report in September 1915 had outlined the University staff’s contributions to the war effort. Some 14 members of the Arts Faculty staff were listed. Amongst these, History’s Professor George Hare Leonard was spending most of his spare time engaged in YMCA work; the Lecturer in History and tutor for women students, May Staveley, a Quaker, had worked over the previous summer with the Friends Relief Commission in France; their fellow historian William Luther Cooper, who had joined the department in 1913 and would later become the University’s first salaried Librarian, was waiting to take up a commission in the Royal Field Artillery. May Staveley was also honorary secretary of the University of Bristol Women’s War Work Fund which, amongst other activities, ran the University Hostel for Belgian refugees.

Captain Mason was a ‘brilliant teacher’, reported the WEA’s regional secretary, with a ‘genial disposition’. He was one of ‘the three brilliant men of my generation’ of LSE students, recalled Baroness Mary Stocks four decades later. The University of Bristol’s Council recorded its ‘deep grief’ at the news. The 8th Gloucesters — mostly ‘untried’ men — had gone into battle at La Boiselle at 3.15 on the morning of 3 July to reinforce the attempt to take and hold the heavily fortified village. Mason was one of the six officers killed that day. The village was secured on 4 July; the battalion’s total casualties by then totalling 302 killed, wounded or missing. ‘A truly bloody scene’, recorded their commander, the village flattened as ‘if the very soul had been blasted out of the earth and turned into a void’. Into that void had gone William John Mason, and his name is recorded on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme. The University’s memorial tablet was unveiled on 4 July 1924 in the Wills Memorial Building by Field Marshall Lord Methuen, who could not resist using the occasion to offer indirect but tart observations on the recently-established Labour government. After the service a trumpeter played the Last Post, the final notes echoing through the corridors of the otherwise silenced building.

W.J. Mason included along with some of The Gloucestershire Regiment’s missing, Thiepval Memoria.l Pier and Face 5 A and 5 B. Source: Ancestry Family Tree.

Sources include Western Daily Press, 20 September 1915, p. 9; 17 July 1916, p. 4; 11 November 1916, p. 4; 5 July 1924, p. 5, National Archives, WO 95/2085/1, ‘8 Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment (1915 Jul – 1919 Mar)’; Adrian Carton de Wiart, Happy Odyssey (1950), pp. 58-59.