Content Warning: This post contains distressing detail on violence and sexual assault.

In the latest of our posts for Black History Month, Taisha Richards, a student of African American history in the Antebellum South, explores the story of Cecila Newsome, an enslaved woman who violently resisted her exploitation and abuse.

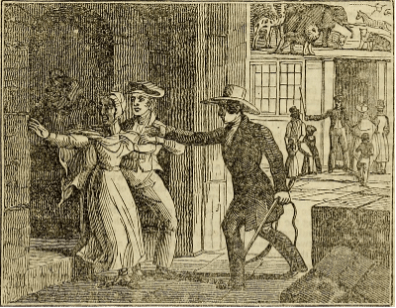

Image from The American anti-slavery almanac (Boston : N. Southard & D.K. Hitchcock; 1838), https://archive.org/details/americanantislav1839chil (Public domain)

Investigations into the experiences of enslaved African American women during the Antebellum period help us to better understand the nature of violence and oppression, as well as resistance. For example, my research into Celia Newsome is representative. After being purchased at the age of fourteen, Celia was raped by her slaveholder on their way to his plantation. Celia unwillingly became his concubine and house slave who he monitored and controlled every aspect of her life. She was sexually exploited for the next five years until she killed her slaveholder after he ignored her pleas to stop assaulting her. This act of resistance resulted in Celia being tried, convicted and executed at the age of nineteen. Celia’s experiences are pivotal to my research because she helps us to better understand the experiences of other enslaved women. She provides an insight into the hidden side of slavery, including sexual exploitation from a young age, being blamed by a slaveholder’s family for the sexual abuse, baring children for slaveholders, and having no legal recourse for exploitation as the law protected their perpetrators. Celia’s story also exemplified that slavery worked on many fronts to subjugate enslaved women by trying to take away their autonomy; however, enslaved women resisted in many ways regardless of the consequences. Celia is important as she was one of many enslaved women who paid the ultimate price with her life because she refused to continue to be sexually exploited.

We asked Taisha, why is this history important to you?

Slavery in Antebellum America has always interested me. My research focuses on the forms of exploitation enslaved women endured, specifically sexual exploitation and how in the midst of being exploited they resisted utilising different forms of agency. Problematic stereotypes like the Jezebel allowed enslaved women to be sexually exploited as they were represented as over sexualised, absolving slaveholders of blame or consequences. I wanted to know about the experiences of enslaved women in their own words

About the Author

Taisha Richards studies African American history and the experiences of enslaved people in the Antebellum South with a particular interest in the intersectionality of race, gender, sexuality and law. Taisha can be found online @TaishaRich