by Prof. Ronald Hutton

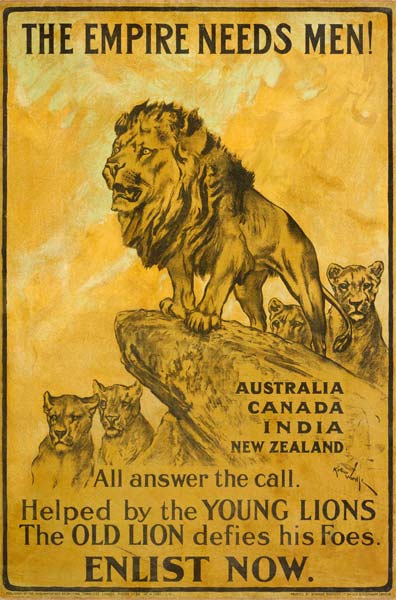

The successive television series on historic farming practices and associated bits of rural life, which commenced several years ago with ‘Tales from the Green Valley’, continues currently on BBC television with ‘The Tudor Monastery Farm’. Each series features visiting experts in particular processes, and I have now appeared in more episodes of the whole sequence than any other, including two-thirds of those in the present one: and I shall duly be present in its ‘Christmas Special’. This prominence is mainly due to the fact that my particular expertise, in the history of seasonal festivals and customs, extends over the whole range of historic time so can fit into any age before living memory. It also, however, owes something to the rapport which I have built up over the years with the company which makes the various series, Lion TV, and with the stars of them. By process of natural selection, an original resident team of five has reduced to two survivors, Ruth and Peter, who are both now television personalities in their own right and superb at their job, just joined for the present series by new boy Tom, who shares Peter’s courage, resilience and geniality.

Television work has been part of my own life since the 1980s, although an intermittent one squeezed into small gaps between my regular duties as a university-based teacher and researcher. As a result, although the occasional long vacation slot or period of reduced teaching allows me to present a series, my classic contribution is the interview, in which I turn up on set for a couple of hours, am filmed giving information on the subject of the programme, and then go back home or to the office. This format fits the Farms perfectly, although the setting for the Tudor Monastery series was mostly in West Sussex and so day trips were usually needed, with different sequences being run together: for example, the Palm Sunday and May Day sequences were filmed on the same date (in June). I usually enjoy my work for the historic farm programmes even more than most of what I do for television, partly because of my cumulative friendship with the stars and the crew, partly because my role as an expert on festivities means that I am talking about, and involved with, fun, and partly because the sets provide a unique chance to reconstruct bits of living history. When I saw what was intended for the Midsummer’s Eve sequence of merrymaking, based on a chapter in one of my books, I had to comment that this was not only going to be the fullest filmed representation of an early Tudor midsummer revel that had ever been made, but probably the most elaborate such revel ever actually staged. The director had put together four different rituals at once, when an English community in 1500 would only have bothered with one. As for the cast, they explained candidly that my popularity with them was due to the fact that every time I turned up, they knew that they were going to get a party, instead of having to engage in yet another difficult, smelly and exhausting job.

All of us agreed that the world into which we were now put was by far the most alien of those which we had recreated to date, in a span between the 1630s and the 1940s. Even the early Stuart Age seemed more recognisable than this one, which was still essentially late medieval, and a quantum leap beyond modernity in its religious, social, technological and political culture. The clothes were utterly unfamiliar, and inconvenient. The custom is that a visiting expert puts on period dress like the cast, even though, as at least one reviewer has noted acidly, I am never asked to cripple myself by removing my spectacles, so the effect is never perfectly authentic anyway. Even so, I was still expected to get myself laced into doublet and breeches, of rough and itchy wool, using sharp metal points on the end of strings instead of buttons. The process takes a quarter of an hour and needs assistance: this is not a job on which a loose digestive system is an option, and even less dramatic natural processes are awkward: we won’t even begin to discuss the techniques of coping with a codpiece. I was also forced to wear stupid hats, which I kept quietly trying to lose, and there were problems of other sorts. Water was not drunk at table or at open-air revels at that middling level of Tudor society, but beer, and a crew who did not seem bothered about my glasses insisted that we had to have it visibly foaming in our mugs. The beer drunk in 1500, however, was thin and weak, and so bearable in quantity, whereas we got provided with strong Continental lager. As many of the party sequences involved constant retakes of eating and drinking scenes, we had to sip very carefully; although in fact I soon found that to some extent slight inebriation was an asset in coping with some of the activities in which we had to engage; to date a unique experience for me in television – or indeed any – work.

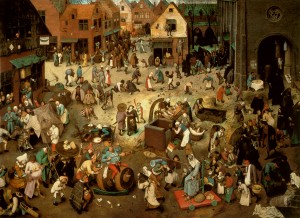

The Christmas Special also involved suffering the smoke of a log fire lit in a replica Tudor house which was never built in the expectation that any fire would actually be kindled there, and so had no structure to remove the fumes. However, there were some truly wonderful scenes. Peter commented at the Easter Day dinner that he had never before ended up in a Da Vinci painting. He was completely right, save that the painting was more that of a Flemish than an Italian artist of the period. There was a moment when the harvest sequence was being filmed, on a gorgeous sunlit September day, when I looked at the cast tying up sheaves in their costumes upon the field, and caught my breath with the beauty of the scene as well as its compelling historical authenticity. Also, I wasn’t the only professional historian making a fool of himself on the series, for my former Bristol colleague Professor James Clark acted as consultant to it, and had to appear at intervals as a Benedictine monk in black habit and sandals. All told I got off lightly, as it was my task to keep viewers reminded that the age of bubonic plague, bloody and futile rebellions and minimal social mobility was also that of Merry England.