In this blog post Dr Daniel Haines, Lecturer in History, considers the role of art in opening new avenues of historical enquiry.

© Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives

© Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives

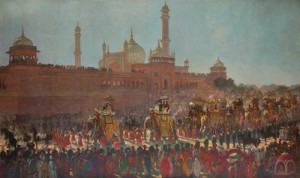

In the relative cool of an Indian winter, a train of elephants lumbers through the heart of old Delhi. Atop one beast are the Duke and Duchess of Connaught, brother and sister-in-law to the British King-Emperor Edward VII. Ahead of him on another are Viceroy Curzon, the King’s representative in India and head of the colonial government, and his wife Mary. Beneath them, both literally and figuratively, uniformed Indians march along a parade route lined by soldiers. The viceroy and his staff have planned every detail of the day’s ceremonies to convey the might and power of the Raj.

This was the scene of the 1903 Delhi Durbar, a spectacular festival held to mark Edward VII’s ascent to the throne. Celebrations continued for another fortnight afterwards. The vista comes to us via an enormous oil painting that dominates the entrance hall at the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, part of the Wills Memorial Building at the edge of the university campus. It’s worth a visit to take in the sheer scale of the painting, which feels virtually life-size when you’re in front of it. The painter has very clearly tried to capture the sense of awe that the Durbar was supposed to instil in Indian attendees, especially the semi-autonomous Indian Princes who collaborated closely with the British.

The history of the painting is also fascinating. It was not the product of a patriotic colonialist, but an expatriate American artist, Roderick MacKenzie. MacKenzie had travelled a long way from his native home in Mobile, Alabama. Originally intending to stay in India only a few years, he became hooked on the subcontinent – like many a backpacker since. This painting, Durbar, the State Entry into Delhi, was only one of dozens that he produced during his financially unsuccessful fourteen years in the country. MacKenzie almost bankrupted himself finishing the painting in London.

Today, the painting continues to provoke discussion. The Museum organised a day-long workshop to discuss it in March, How to interpret Art and the British Empire for 21st-Century Audiences: Roderick MacKenzie’s Delhi Durbar of 1903. Representatives from community groups and the British Museum as well as Bristol University’s Department of History discussed how we today can make sense of an artwork that borders on the monumental. Is it art or history? Should we appreciate it as a magnificent aesthetic accomplishment? Should we condemn it as piece of imperialist propaganda?

These kinds of question apply to any product of Europe’s imperial heyday. Studying this period of history is controversial: strong opinions abound about how people in former colonial countries, as well as those in formerly colonized countries, should interpret empire’s legacy. Whatever your position, there is no denying that empire is a key part of British history. How we relate that to modern British identity is not far removed from aggressive public debates about the commemoration of WWI that swept the national media in 2014. There are no easy answers. But standing, dwarfed, in front of MacKenzie’s giant canvas, is a powerful call to opening up the questions.

You can see a high-resolution version of the painting by clicking on the image in this link: http://www.bristol.gov.uk/press/leisure-and-culture/delhi-durbar-painting-show-city-museum-and-art-gallery

A brief bio of MacKenzie is here: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1786