History takes time. As historians, we can spend years on a piece of research: reading the work of other scholars, visiting archives and libraries, and writing our findings into books and journal articles. Once that’s done, more time passes. It can often take a few more years for a book or article to make it into print. It sometimes all feels like a terribly slow process.

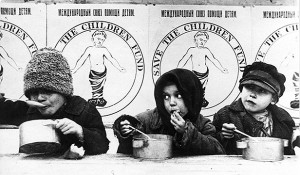

My research is on people who work quickly: humanitarians. I explore the efforts made by NGO Save the Children to aid children in the conflict-riven early-twentieth century. Seeking to halt the spread of disease, feed starving populations and shelter millions of refugees during and after two world wars, humanitarians could not work fast enough. Delays cost lives.

I want the research that I’ve done into past humanitarian principles and practices to help contemporary NGOs to reflect upon what they do in the present day. Yet, moving constantly from crisis to crisis, now, as in the past, humanitarian organisations have little time for refection.

Lengthy journal articles and detailed monographs aren’t appropriate ways to communicate with busy humanitarians. If we want to work with NGOs, historians need to find different ways to speak about the past. To do this, I recently gave a short talk about my research to the Global Programmes Leadership Team at Save the Children. (After I’d spoken, the discussion was moving on to Ebola prevention strategies and the Syrian refugee crisis. I certainly didn’t want to take up too of the meeting!) Although time was short, the audience were interested. History is a key feature of Save the Children’s organisational identity. Its staff has a proud sense of the heritage of the organisation, which was founded in 1919 as one of Britain’s first ‘international’ charities.

Like many humanitarian organisations, Save the Children has turned its history into a compelling ‘origins story’ through a focus on a single ‘great individual’, Eglantyne Jebb. The story goes that the saintly Jebb created Save the Children after the First World War as an expression of her unique vision of compassion and concern for ‘all the world’s children’. This ‘origins story’ is not just an oversimplification. It’s actually wrong. Save the Children was formed not by Jebb, but by her younger sister, feminist socialist Dorothy Buxton. Its early work expressed not only ‘compassion’, but also Buxton’s radical vision of international solidarity.

By remembering Eglantyne Jebb as its founder, rather than her radical sister Dorothy Buxton, Save the Children has promoted a myth about the nature of humanitarian work: that it should be uncontroversial and apolitical. In fact, for Save the Children’s founder Dorothy Buxton, concern for others could not be separated from broader critiques of the structures and systems which have caused their suffering.

As a historian, it certainly isn’t my job to advise on present day humanitarian policy or practice. But, by demythologising the past, perhaps what I can do is free NGOs up to think in new ways. If we accept that the humanitarian mission was, at its inception, deeply political, this may enable present day organisations to understand their work as radical and themselves as challenging not only the effects of poverty, but also its causes. By focusing my talk to the Global Programmes Team at Save the Children on the life and legacy of Dorothy Buxton, I could open up a conversation about the nature of humanitarianism in the present day.

In their recent History Manifesto,Jo Guldi and David Armitage argue that in order for history to have impact beyond the academy, historians should focus on big picture, longue durée histories. Communicating with Save the Children I did the opposite. I used a short life-story, told quickly, to ask important questions to busy people.