During a recent visit to Malta, Research Associate, Dr Andrew Hillier, found a country seeking to establish its identity in the post-colonial world.

Save for the odd passing reference, Malta tends to go un-noticed in British imperial history. Yet, for over 150 years, the island, together with neighbouring Gozo, was an important British colony, playing a key role in the empire’s Mediterranean strategy. Moreover, when the country finally gained its independence, this ended not just British rule but two thousand years of colonisation. Its history, therefore, is instructive as to both Britain’s imperial project and, more generally, the impact of imperial rule on a nation and its people.

Whilst, according to the standard narrative, the Maltese have been Christian ever since St Paul’s arrival in 60 A.D., they may have converted to Islam during the period of Arab rule (8th to 11th century). Certainly, Arabic influence can be found in the local language, which is still widely-spoken, and in some of the architecture, which, though of a later date, has echoes of the Arabic style, particularly in the former capital, Mdina. [i]

However, since the Arab departure, the country has been inextricably linked to the church in Rome, beginning with some 400 years of Norman, Angevin and Aragonese rule, and followed by that of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem, who were ceded the island by Charles V in 1530. Whilst Catholicism predominated, the key characteristic throughout this period was the authoritarian subjugation of the island’s indigenous population. Restricted to administering their local affairs, they were considered useful only for paying taxes and providing services to the colonial rulers. Although the Knights are celebrated for leading a heroic defence of the island against the Turks in the Great Siege of 1565, their presence was always resented. When Napoleon landed in 1798 and persuaded them to leave, he was initially well- received. However, he flattered only to deceive and, for the next two years, his army embarked on an orgy of plunder and pillage, before an uprising led to his expulsion.

Not surprisingly, the British were warmly welcomed, the royal coat of arms over the portico of the Main Guard recording the granting of the country ‘by the desire of the Maltese and with the consent of Europe’. However, whilst the island was crucial to the defence of the eastern Mediterranean and the route to India, there was no sense of imperial mission. Ruled by a governor and his officials, the Maltese were confined to the more junior posts in the public services and the armed forces and had no significant say in the running of their country. Although the economy prospered, it was a period of dignified subservience, punctuated only by the odd incident of imperial insensitivity. For example, in 1912, the Royal Navy caused great offence by inexplicably re-naming its headquarters at Fort San Angelo, HMS Egmont, and, only twenty years later, in a placatory gesture, changed this back to the somewhat incongruous-sounding HMS San Angelo.

It was the Royal Navy and the island’s superb fortification system, strongly reinforced in the aftermath of the Great Siege, that enabled the Maltese to mount a heroic resistance against Germany during the Second World War, one that resulted in appalling hardship and the award of the George Cross, still an important reminder of the solidarity between Britain and Malta at that time. After the war, a plummeting economy fuelled an intense but always peaceful drive towards independence. Achieved in 1964, for the more radical element, the country only truly became free when the Royal Navy and other NATO forces withdrew on 31 March 1979, now celebrated as Freedom Day. Although this dealt a severe blow to the economy, through tourism and various commercial initiatives, by 2004, it had recovered sufficiently to be admitted as a full member of the EU and the Eurozone.

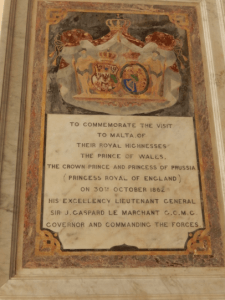

From this complex history, it is difficult to disentangle the multiple influences that have shaped Malta’s identity. English remains widely-spoken and scattered through the island are references to Britain’s presence, in particular in connection with the war. However, whilst there is the odd statue and memorial plaque, there is little evidence of the architecture so familiar in its other colonial settings.

Emblems of Britain’s Imperial presence, Valetta

Inspired by the Palace of the Grand Masters and the Knights’ auberges, the principal buildings, constructed in the local honey-coloured limestone, are mainly of baroque design.

For the rest, the style and mood is quintessentially Mediterranean in a country with an extraordinarily rich cultural history, one that boasts the oldest standing temples in the world at Tarxien (3600-2500 BC), an outstanding Museum of Archaeology and an exquisite mosaic from the Roman era. Supported by generous EU grants, there is a substantial programme to promote this heritage.

If this all contributes to a new identity, the country is also grappling with major issues. The government has recently closed its borders to more refugees, it has been accused of a cover-up in relation to the murder of the investigative reporter, Daphne Galizia, and has been heavily criticised for selling citizenship to anyone who can afford the extortionate fee.

Lamenting what he sees as a cynical commercialism, one commentator has suggested that the people ‘have lost their Maltese soul’: ‘we have always welcomed foreigners amongst us, be they imposed without our consent or as refugees from conflict or persecution…It was because we were friendly, generous, warm and altruistic’. But, he argues, ‘we have forgotten the meaning of solidarity and need to ask, “am I still truly Maltese?”’[ii] Others, however, consider this as no more than the birth pangs of a young nation, slowly emerging from a long history of colonial exploitation.

It seems clear that, whatever the outcome, Malta’s identity will be forged within the framework of the European Union, which has given it the confidence to assert itself as a nation. The geo-political wheel has turned full circle and it now has the right to veto whatever terms are proposed by its old imperial master for leaving the E.U.

[i] All photographs by the author taken in July 2018

[ii] Anthony Buttigieg, ‘Are we still truly Maltese’, The Sunday Times of Malta, 8 July 2018, p.19.

Pingback: How historical fiction writers have merged human experiences with factual accuracy – ToLearnLanguages.com

Pingback: How historical fiction writers have merged human experiences with factual accuracy - H10 News

Pingback: How historical fiction writers have merged human experiences with factual accuracy - Azad Kashmir

Pingback: How historical fiction writers have merged human experiences with factual accuracy - The Maktab Times

Pingback: How historic fiction writers have merged human experiences with factual accuracy -