As President Trump endorses a bill to restrict immigration, Lecturer in North American History, Julio Decker, reflects on the history of US attitudes to the ‘huddled masses’.

Much of what has been happening since the American election last year seems novel and unprecedented. It seems difficult to remember a single week of the Trump administration that did not collide with political customs. Last week, another seemingly unprecedented break with the past happened when White House Aid Stephen Miller declared that Emma Lazarus’s poem ‘The New Colossus’, engraved in the pedestal, was irrelevant as it was added after the Statue of Liberty had been erected. In a heated exchange with CNN’s Jim Acosta, he defended President Trump’s support for a Senate Bill that would halve the number of legal immigrants allowed to come to the United States. The bill would test potential migrants’ job prospects before admission, among them their English-language skills.

For many commentators, this seemed like a new low: denigrating a poem that stood for the American tradition of calling for the world to send ‘your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free’. And there is a case to make that Miller misrepresented the poem, which was written as part of a fundraiser for the statue, thus being explicitly connected to the Lady of Liberty. But Miller did get one thing right: opposition to immigration, and to the poem and what it represented, was not a break in American history: it had existed even before 1903 when the plaque with the poem was installed. Just like the travel ban, the Trump administration’s immigration policy proposals have such a clout because the restrictionist impulses have a long tradition in American history.

Lazarus wrote the sonnet in 1883, one year after Congress had passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned – with only a few exceptions – an entire nationality from entering the United States. Opposition to immigration was not limited to those from Asia: when the origin of most new arrivals started to shift from North-western to South-eastern Europe in the 1880s, many Americans started to demand restriction. These nativist voices explicitly rejected the spirit embodied in ‘The New Colossus’ – new immigrants were depicted as lowering wage levels, being unwilling to assimilate, and lacking the cultural knowledge to participate in a democratic society. In the late nineteenth century, these views were framed in contemporary racial theories – new immigrants were classified as part of the Alpine or Mediterranean races, supposedly inferior to Anglo-Saxons.

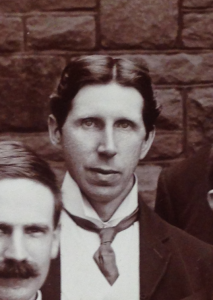

From the 1890s, nativist voices began to be heard in Washington. Conservative think-tanks and lobby groups such as the Immigration Restriction League built alliances with farmers, Southerners, and labour unions. Influential Senators such as Henry Cabot Lodge started to lobby for new means of reducing immigration. What university degrees, skills, job prospects, and language skills are to conservative lawmakers today, the literacy test was for nativist reformers of the early twentieth century. At Ellis Island and at other inspection sites at American borders, immigrants were meant to prove that they could read and write. Restrictionists argued that the test was impartial, and that apart from testing a crucial skill for participation in American politics, it would also exclude the most undesirable, as illiteracy supposedly correlated with criminality, poverty, and dependence on state aid. The real motivation, however, was another correlation – that illiteracy was the lowest among people from North-western Europe. Depending on the audience, restrictionists would openly address this racial dimension– the founder of the Immigration Restriction League, Prescott F. Hall, declared in 1919 that immigration restriction should be seen as a method of keeping ‘inferior stocks’ from ‘both diluting and supplanting good stocks’.

Henry Cabot Lodge. Image by John Singer Sargent – National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Public Domain.

For most of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, however, Presidents rejected the ‘radical departure from our national policy’, as Grover Cleveland wrote when he vetoed a literacy test bill in 1897. Woodrow Wilson vetoed similar bills in 1913 and 1915. Furious with the President’s threat of a veto, Senator Lodge declared that instead of clinging to the tradition embodied by ‘The New Colossus’, he should read Thomas Bailey Aldrich. In 1893, this poet had written ‘The Unguarded Gates’ as a reply to Lazarus, bemoaning that the nation let in ‘featureless figures of the Hoang-Ho, Malayan, Scythian, Teuton, Kelt and Slave’, who brought ‘with them unknown gods and rites’. The poem called out to Lady Liberty to rethink her welcome to the world:

In street and alley what strange tongues are loud,

Accents of menace alien to our air,

Voices that once the Tower of Babel knew!

O Liberty, white Goddess! Is it well

To leave the gates unguarded?

Lodge was not the first to bring Aldrich’s poem into political debate – it was popular among restrictionists. While citing it did not convince Wilson in 1913, the nativists’ lobby work did eventually pay off when the United States entered World War One. Public doubts over immigrants’ loyalties helped restrictionists to organize the Congressional votes necessary for overriding another veto by Wilson. In 1917, the new Immigration Act included the literacy test. It also banned all immigration from the so-called Asiatic Barred Zone, stretching from the Ottoman Empire to New Guinea. While this wholesale ban excluded migrants regarded as non-white, the literacy test proved to be less effective than originally envisioned. In the 1920s, a wide coalition of Democrats and Republicans passed acts establishing a quota system which drastically limited immigration from South-eastern Europe. Like today, the radical anti-immigrant rhetoric was supported by the White House. ‘American liberty’, vice-president Calvin Coolidge wrote in an article for Good Housekeeping in 1921, ‘is dependent on quality in citizenship’. While the ‘Nordics propagate themselves successfully’, he wrote, in the question of limiting immigration ‘racial considerations [are] too grave to be brushed aside’. It is only ‘when the alien adds vigor to our stock that he is wanted’ – to ensure national progress, racially inferior immigrants therefore had to be excluded, he argued.

Symbols like the Statue of Liberty are imbued with political meaning. For many liberal Americans, the statue stands for an American tradition of welcoming immigrants regardless of English-language skills, race, or ethnicity. But the statue so many immigrants saw on their arrival to New York also embodies another powerful strand in American politics, one those with a positive view of the United States tend to repress. Immigration legislation was also shaped by a strong tradition of nativism, racism, and conservatism, one that politicians can mobilize when calling for tighter regulation. In their vision of American history, Lady Liberty was wrong in welcoming the world’s poor and huddled masses – this is why ultra-nationalists interpret the latest Vogue cover as a criticism of the Trump administration. Understanding this history gives us a stern warning: when this tradition is embraced by the White House, consequences for immigrants can be dire.