An institution is comprised of more than just buildings, hierarchies or symbols. When the University of Bristol was founded in 1909, its managers and patrons rushed to explain its purpose in terms of what it stood for: a common culture – an attitude – of excellence, improvement, and civic responsibility. But these are just fine words until they are given meaning by real people actually enacting these values, promoting and defending them.

Today – graduation day – is a very important day for University of Bristol historians. One of the ways we celebrate our students’ success is through the award of prizes for high attainment. The George Hare Leonard Prize is awarded to the graduate with the best overall performance, but who was George Hare Leonard, and what does the fact that we attach his name to such a prestigious award mean?

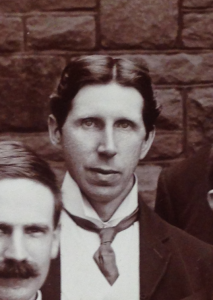

Born in Clifton, Leonard took his BA and MA in History at Cambridge, returning to Bristol to deliver the Cambridge Extension Lectures in the 1880s and 1890s. He was eventually appointed Lecturer in History at University College Bristol in 1901, rising to the rank of Professor in 1905. Only one one other candidate was interviewed for the professorial job: Frederick Maurice Powicke, who would go on to rise to the very top of his discipline by becoming Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford.

But Leonard was something special, and everybody at University College knew it. The College’s great patron, John Percival, the Bishop of Hereford, remarked in 1908 on the ‘good work’ that he and ‘the younger teachers’ were doing there. This stood in contrast, Percival claimed, to ‘older professors’ who had ‘lost touch with the working classes’. Leonard’s retention as professor came at just the right time to make a real impact, for in 1909 the College became the University of Bristol. At this institution Leonard stayed until his death in 1941.

There is much to celebrate about Leonard’s life, and his contribution to our institution, our discipline, and our city. Four highlights may serve to underline why he is worth remembering.

First, he used his professorship to reinvigorate the intellectual quality of historical studies at the College by introducing a new syllabus in the 1906/07 academic year. For the first time ever at Bristol, students were expected to become acquainted with primary sources directly, and to engage in a dialogue with their lecturers. Out went grand lecture series which tried to locate the greatness of the English psyche in the misty forests of fifth-century Saxony; in came the latest historiography, original documents, and a spirit of common intellectual purpose. These are the principles which still form the core of the degree at Bristol today, where our students are encouraged to form their own opinions, and to share and defend them in rigorous but collegiate seminars.

Second, he held a firm belief that the production of historical knowledge was an endeavor of real value, arguing that history ‘cast light on modern problems which engross the attention of all thoughtful men’. We encourage all our students to consider the purpose of what we all do and, whether we agree with Leonard or not, the willingness to engage in critical self-reflection is an important skill which we try to encourage all at Bristol to adopt. Above all we want our graduates to be self-confident in the value both of their discipline and of their own beliefs and ideas.

Third, he was strongly committed to the equality of all persons. While holding his professorship, he headed up a committee and acted as fundraiser-in-chief for the erection of a memorial to Mary Clifford, a nineteenth-century campaigner for women’s welfare, in Bristol Cathedral. This was neither an easy nor a meaningless gesture: in the 1910s, attacks on Suffragette headquarters in Bristol were widely reported in the national press. Leonard was a person willing to speak out, but perhaps more importantly, to put his ideas into action.

Fourth, he ‘gave himself heart and soul to the cause of adult education’, according to the writer of his obituary in The Times. This was an accurate assessment. Not only did Leonard frequently hold the management of the University to account on the issue of ‘educating the working men and women’ of Bristol, but he also gave up what little time he had spare to read their poetry, respond to their letters, or even go rambling with them – even if they were not registered students. At Bristol today, we celebrate continuing education and aspire to widen access as far as possible, because we see that education can have a transformative impact on peoples’ lives.

So, when we award the George Hare Leonard Prize today, we do more than just remember one of our department’s ancestors. We celebrate a great historian, certainly, but we also recognize a set of timeless values which bind us together – staff, students, and graduates alike. We celebrate both individual excellence and a collegiate spirit, the importance of rigour, but also the enduring value of historical thinking. In offering an award in Leonard’s name, we look not a committee to define our values for us, but to our own past.

Special thanks to colleagues in the University of Bristol’s Special Collections, who helped to identify some of the sources which form the basis of this judgment: Leonard’s own correspondence, that of the Bishop of Hereford, Calendars of the University College Bristol, and various newspaper cuttings.

Dr John Reeks, Teaching Fellow in History.