In the wake of Canada Day, Dr John Reeks looks at the war work of Canadian-born University of Bristol historian Charles M. Macinnes.

Charles M. MacInnes, known to his friends as ‘Mac’, joined the University of Bristol in 1919 as Assistant Lecturer in History. A Canadian by birth, and despite being nearly completely blind, he rose quickly through the academic ranks. In 1922, he was awarded £20 for research into the history of the tobacco trade and thereafter started to take on a number of research students in the fields of colonial history, the history of slavery, and British political history. He published widely on these subjects, including his first book, The Early English Tobacco Trade, published in 1926, and his 1934 England and Slavery, which made the case that ‘much remains to be done’ to eradicate the evil practice from human society. Following the death of Professor Robert B. Mowat in a plane crash in 1941, MacInnes was promoted first to a readership and then to the professoriate, subsequently becoming Head of History in 1943, before finally rising to take the Deanship of the Faculty of Arts in 1952.

In retirement, MacInnes wrote several more books but one is particularly notable: 1962’s Bristol at War, an account of the city’s reaction to, and suffering during, the Second World War. It is, by professional standards, a failure. MacInnes was clear at the outset that he wanted to avoid writing a book aimed at scholars, or in other words, ‘a trickle of text running through vast meadows of footnotes’. This he certainly achieved. Bristol at War is both readable and instructive, informing the reader about the vast civic undertaking that constituted Bristol’s war effort, whether that be the work of the Women’s Voluntary Service in training ambulance drivers and receiving troops evacuated from Dunkirk, or the Lord Mayor’s War Services Council, which raised and expended nearly £100,000 for a variety of wartime causes between 1940 and 1945. The book in nonetheless nothing short of being a whitewash. One crucial individual is consistently and deliberately written out of Bristol’s wartime history, a person who had won widespread plaudits for his labours at the time and had even been awarded a CBE for his efforts in the 1959 New Year’s Honours. That figure was MacInnes himself.

Bristol Archives hold sixteen large folders of letters and documents which MacInnes had collected in the process of compiling materials for Bristol at War. Organised thematically – ‘Anglo-American Relations’, ‘The Lord Mayor’s War Service Council’, ‘Bristol Information Committee’, and so on – they closely parallel the chapters of the book itself. Upon opening the files, though, it becomes quickly apparent that many of these letters are coming into and going out of MacInnes’s own offices at the University: despite not awarding himself a single mention in Bristol at War, not even the briefest of footnotes, MacInnes himself was at the very heart of Bristol civil wartime operations. I shall take just three examples of his involvement, though there are many more.

First, he was a member of the Bristol Information Committee and convened a subcommittee tasked with improving civilian attitudes to the evacuation of children during the Blitz. During the so-called ‘Phoney War’ of summer 1940 the problem of children returning to the dangerous city caused a great deal of anxiety among Bristol’s political leaders. In a letter of 3 March 1941 to Phyllis Forbes-Dennis, who was seeking to draw inspiration for her own campaign in Plymouth, he explained that ‘it has been my function to disseminate information by means of loud-speaker vans for various authorities’. He went on to explain that his present preoccupation was drawing up a report on morale in Bristol, which could be used to inform the decisions then being made. The subsequent report found its admirers on Bristol’s Council, in the offices of the Regional Information Committee, and the Ministry of Health. Not content with academic investigation, he took practical steps, including organizing twenty Christmas parties – for thousands of Bristol’s citizens – in the winter of 1940. MacInnes also saw to it that ‘travelling troops of players and entertainers…will be visiting bombed areas’ in an effort to boost morale. These parties and entertainments were extremely successful. On 13 August 1943, H. V. Hindle, Secretary to the Lord Mayor’s War Services Councils, wrote to MacInnes to explain that despite cutting back on ‘air raid recuperative work’, the committee ‘strongly felt that the Christmas parties for old people and children should still go on’.

Second, he was at the fore of efforts to improve understanding and to promote friendship between the people of Bristol and the citizens of Allied nations, many of whom, especially the Americans, were now stationed in Bristol itself. One such initiative was the organization of lecture tours, in collaboration with civic organisations like the Rotary Club and the main political parties. ‘The object of these lectures’, MacInnes explained in a circular dated 29 June 1940, was to ‘strengthen the morale of the civil population’ and to promote ‘the feeling of confidence as to the issue of the war’. As the years rolled on, the lectures increasingly focused on the contributions of Britain’s allies and speakers encouraged Bristol’s citizens to return the kindnesses that had been shown to them in the dark days of the Blitz. MacInnes was a person to whom Bristol’s great and good would always answer the call. When he convened an unofficial meeting at the University in February 1943 to discuss the deteriorating relationship between the city and American merchant seamen stationed there, representatives from the Bristol Port Authority, the W. V. S., the Ministry of Information, and the American Red Cross were all in attendance. He was also not above writing speculative letters to foreign ambassadors and consuls, in the hopes of procuring useful materials for his activities. In a 1943 letter to Canada House, for instance, he suggested putting on so-called ‘Canada Parties’ in Bristol: ‘it would be nice if…the Canadian touch could be in evidence’.

Third, he capitalised on his academic connections to organise recuperative holidays in Oxford for heavily-overworked and war-fatigued Bristolians during the autumn of 1941, particularly those living in dangerous parts of the city. In all, approximately 7,000 citizens took advantage of the scheme, which saw them placed in Oxford colleges for a two-week period. There, they could sight-see, play a game of cricket, or merely relax in a park or quad. So successful was the ‘Holidays in Oxford’ scheme that it made the national press, with the Daily Express reporting on 13 July 1941 that Bristol’s ‘soldiers of the Home Front…are being led into peace’ by Charles M. MacInnes, a ‘jolly, red-faced man of nearly 50, with blue eyes, shaggy hair, and tons of determination’. In all, the scheme cost nearly £20,000, though some colleges like Oriel were so happy to help that they refused to charge a penny. In MacInnes’s own words to the President of Magdalen in a letter of October 1941, the scheme ‘will help substantially to maintain public morale no matter what disasters may befall us…Bristol will always be grateful to Oxford for what it has done’. Similarly, one might add, Bristol owes a debt of gratitude to ‘Mac’ himself, without whom none of this would have been possible!

Yet, when he came to write his memories up in Bristol at War, MacInnes systematically removed himself from the story. Christmas parties had been organised ‘by the aid of the Lord Mayor’s grants’; the success of the Oxford holidays was simply attributed to the fact that ‘Bristol’s connection with that University in the past had at times been intimate’. The Lord Mayor gets the credit for tirelessly ‘reminding American friends that men from the old city on the Avon were the first Britons ever to set foot in the New World’. Even the ubiquitous loudspeaker vans appear from nowhere, and are simply described as having been ‘at the disposal [of the Ministry of Information]…manned by voluntary drivers and broadcasters’. Quite why he did this is unclear: perhaps through scholarly reluctance to write about himself, or perhaps because he was possessed of an almost super-human humility.

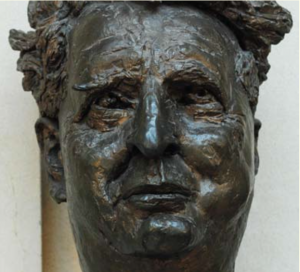

Picture 2: Bronze Bust of MacInnes by Jacob Epstein, Bristol City Art Gallery. No known copyright restrictions.

The upshot is that MacInnes is remembered in the documents but not the history. The evidence of his involvement in the civic war effort is everywhere in the archives, but nowhere in the books and articles. A profile in the University of Bristol’s centenary edition of the alumni magazine Nonesuch ironically mentions the fact that MacInnes was ‘well-known for his Christmas parties’ without passing comment on the many thousands of ordinary citizens who benefitted from them during Britain’s ‘darkest hour’. It carries a photograph of the 1957 bronze bust of MacInnes produced by Jacob Epstein without questioning why the pioneer of modern sculpture would be commissioned to honour a mere Professor of History. The blame for these omissions ultimately lies with MacInnes himself. Perhaps the truth is that ‘Mac’ was uniquely ill-placed to write the history of Bristol at war: too close to events, too intimately involved, and too modest, to write an honest account of what transpired. His braille typewriter, which had such a good war in Mac’s hands, was employed in his retirement to write an incomplete and ultimately highly misleading piece of history. ‘Bristol at War’ still awaits its historian: so too does Charles MacInnes.

The following sources have been consulted:

Charles M. MacInnes, Bristol at War (Museum Press: London, 1962)

Bristol University Library, Special Collections, Faculty of Arts Minute Books, DM2287/3/4

Bristol Archives, Papers of Professor Charles M MacInnes, 11757/1-16

Nonesuch, Spring 2009, Issue 2