Grace Huxford, who joined the department as a lecturer in nineteenth/twentieth century British history in September 2015, reflects on reading letters and diaries in historical research:

For a number of years, my New Year’s Resolution was to keep a diary. Like many would-be diarists, I always started well; the first couple of weeks of January contained detailed descriptions of my day, who I had talked to, what music I had listened to, what I had eaten. But by February my entries would fizzle out and the notebook would go back in a drawer for another year. Apart from providing snapshots into my rather mundane activities in January (and the phenomenon of New Year’s Resolutions), I imagine that my diaries would be of little interest to future historians. Furthermore, I would be mortified if these diaries were to ever to reappear – even more so, if they were to reappear in a published format, like an article or book. Last year, many famous diarists noted how they were appalled at reading their old diaries once again. Recalling these attempts at diary-writing always prompts me to think: how should historians treat ‘private’ documents like letters and diaries? Even those which are publically available via archives?

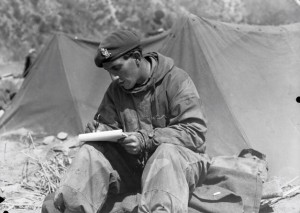

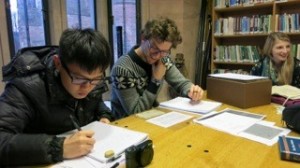

In researching the experiences of British servicemen during the Korean War (1950-1953), I have read a great number of other people’s diaries, as well as personal letters sent from serving soldiers to their loved ones: letters from husbands to wives, boyfriends to girlfriends, fathers to children, sons to parents. Understandably, the tone, length and content of these letters varied greatly. One letter from a prisoner of war held in China contained a picture of a dog for his four-year-old child (something that could not be objected to by the censors at the prisoner of war camp). Elsewhere, fathers at home in Britain wrote to their sons (many 19-21 year old National Service conscripts served in Korea) about their own experiences in the Second World War and their advice for keeping warm, happy or busy. Many young National Servicemen also wrote to their mothers, asking for socks and magazines to be sent as soon as possible.

In one particular set of letters a young conscript told his fiancée (in great detail) about the silk stockings he had bought her when on leave in Japan. When reading such material, I was reminded of the diary theorist Julie Rak’s comment that we are all ‘voyeurs when we read the diaries of others’.[1] In the most personal letters, the researcher becomes deeply aware that the letter is the full extent of that relationship at a given time – what sociologist Liz Stanley has called ‘a simulacrum of presence’.[2] Some letter writers were even told to give as much detail as possible: in 1945 psychologist Kenneth Howard advised army wives writing to their husbands that ‘[n]o scrap of news, of domestic detail, of friends and of local events is too trivial to be interesting. These things make him feel that he belongs, that he is still there and in touch with all that is going on.’[3] The letter was thus a microcosm of an entire relationship and the social world the soldier had left behind. In this case, the historian feels even more like a ‘voyeur’.

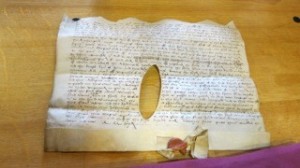

But perhaps viewing letters and diaries as ‘private’ and beyond the ethical realms of the historian is to misunderstand this material. Scholars of diary writing in the Soviet Union (such as Jochen Hellbeck) have noted that it is inaccurate to see a diary or a letter as a purely private space, because ‘selfhood’ in this context was neither private nor public. People used diaries to cast particular public roles for themselves or (as in the case of war) to reflect on public, geopolitical events. Furthermore, they always anticipated a future reader, even if it was just a future version of themselves. Neither are letters simply just between two people – in the 1950s, as in earlier periods, letters were read aloud, shared around family members or even published in newspapers or newsletters (as in the case of some British POW letters from Korea).

So perhaps reservations over using publically-accessible, willingly-deposited letters and diaries is nothing but squeamishness on my part. As I put my diary back in the drawer for yet another year, I think it is important to remember that as historians we should interrogate not just the content of a diary or letter, nor just the context of its production, but what that source represents to both the writer and the reader (and the historian).

[1] Julie Rak, ‘Dialogue with the Future. Philippe Lejeune’s Method and Theory of Diary’, in Philippe Lejeune (eds Jeremy D. Popkin and Julie Rak; trans. Katherine Durning), On Diary (Honolulu, 2009), p. 20.

[2] Liz Stanley, ‘The Epistolarium. On Theorizing Letters and Correspondences’, Auto/Biography, 12 (2004), p. 208

[3] Kenneth Howard, Sex Problems of the Returning Soldier (Manchester, c. 1945). p. 59.