Abigail Le Fevre, Third Year Historian, reflects on her recent studies of Genocide in history:

There will always be a fascination with the morbid. Its ability to represent something familiar yet challenge what we perceive to be ‘normal’ continues to capture the interests of many. Consider the following extract taken from Why Bosnia, containing an interview with a Serbian Officer from the Balkan Wars.

‘Look, there are some things you don’t go around telling everybody. But I’ll tell you, it’s not a pretty sight to watch a circular saw go through human flesh. The way it snarls through the bones.’ [1]

Retelling his involvement in the massacre of Muslim minorities in the village of Zvornik- Bosnia, the Serbian official’s rhetoric is striking. This quote, which I encountered for the first time while studying the Bosnian genocide this term, evoked a sense of shock and anger that was difficult to separate from an analytical mindset. When one finally overcomes the graphic imagery, however, the quote is able to reveal much more than the physical act of killing. We, as historians, are given a unique opportunity to gain an insight into the mindset of a perpetrator, to try and provide an answer to the unanswerable question within genocide- why?

Would it be correct to suggest that the mind of a perpetrator evolves during childhood as argued by Steven Baum? [2] Would we side more with Christopher Browning who argues that perpetrators are often ‘ordinary men?’ [3] Or do we see such behaviours as psychotic impulses displaced into forms of wide spread violence?

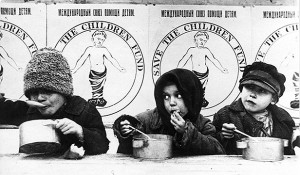

Studying genocide this year has reminded me that the darker areas of history can be highly emotive and personal. Close engagement with oral testimony has the ability to re-personalise large narratives such as that of the Holocaust, the Rwandan genocide or the Cambodian genocide. By actively researching and seeking out answers to the ‘why’ question, I felt my own attitudes starting to be challenged too.

In a context in which a ‘national, ethic, racial or religious group’ was being ‘destroyed’ with ‘intent’, as outlined by the 1948 UN Genocide Convention, what category would I find myself in? [4] Would I become a bystander, witnessing events from afar to protect social upstanding, a rescuer, or even a perpetrator? While I don’t think one can ever fully have a response to this, it remains true that studying genocide with these questions in mind is just as important as the analytical ones. Looking closely at genocides throughout the twentieth century this term has taught us not only about the past, but also about ourselves.

[1] R. Ali and L. Lifschultz (eds.) Why Bosnia? Writings on the Balkan War (Connecticut, 1993), 101.

[2] S. Baum, The Psychology of Genocide: Perpetrators, Bystanders, and Rescuers (Cambridge, 2008), 123.

[3] C. Browning, Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 11 and the Final Solution in Poland (Chicago, 2001), 75.

[4] A. Hinton, Genocide: An Anthropological Reader (Oxford, 2002), 43.