by Dr. Robert Skinner

There is no single word that inspires debate amongst historians more than ‘inevitability’. Nothing, many learned scholars will proclaim, is inevitable in History. Except, inevitably, death.

The world has lost one of its greatest heroes. Perhaps – we might surmise – one of the last heroes, a witness to the passing of an age where hope and progress were seen as guiding principles rather than questionable meta-narratives. But without doubt, one of the single most significant individuals of the past century. As such we are, as Historians, obliged to consider his legacy, his contribution, the multiple meanings of his life and struggle.

I do not believe that the time is right for extensive analysis and off-the-cuff opinion. Our task as scholars is, I think, partly to maintain the integrity of the carefully considered account, of the value of slow reflection in an age of flashing mirrors. In the case of Nelson Rohilhlahla Mandela, though, I feel compelled to offer a couple of partial and provisional thoughts in order to honour the man himself.

Mandela was an African Freedom Fighter

Early in 1962, Mandela slipped across the border into Botswana (then still Bechuanaland), leaving the country of his birth for the first time. His mission was to lead the ANC delegation at the conference of the Pan African Freedom Movement for East, Central and Southern Africa in Addis Ababa, and at the same time develop a network of contacts for the ANC (and military support for MK, the armed wing of the ANC) on the continent. From Botswana he flew to Tanganyika, where, he later recalled, he felt ‘truly home for the first time’.[1] Firsthand experience of independent Africa underlined some of the traditionalist assumptions that he inherited from his eastern Cape upbringing, but set them within a pan-African framework. The liberation of South Africa was, however, the task of the people of that country: the ‘centre and cornerstone of the struggle for freedom and democracy in South Africa’, he argued in his speech in Addis Ababa, ‘lies inside South Africa itself’. Furthermore, he used the speech to force home his message that liberation could no longer be achieved by non-violent methods alone: ‘a leadership commits a crime against its own people if it hesitates to sharpen its political weapons when they have become less effective’.[2]

This was Mandela’s baptism as an international figure. It was a carefully-crafted speech, a collaborative effort whose editors and co-authors included Oliver Tambo, Robert Resha and Tennison Makiwane. But it was an early glimpse of Mandela the statesman – and a reminder today that his political charisma was potent before his three decade-long imprisonment. Robben Island may have made Mandela the great champion of reconciliation, but his fearsome integrity after 1990 also derived from his historical role as an African freedom fighter who – albeit briefly – walked the international political stage at the dawn of post-colonial Africa.

Mandela is a symbol

One of the most intriguing and little-mentioned aspects of the ANC’s tribute to Mandela yesterday was its acknowledgement of his membership of the South African Communist Party. The question of Mandela’s role in the SACP has been hotly debated for half a century, in part perhaps because of his rather careful denial of the fact during his Rivonia Trial statement in 1964. Unpacking and interpreting Mandela’s political ideologies is a task for the future (albeit one that has already been the focus of much considered attention). For now, I would offer the comment that Mandela’s membership of the Communist Party, and the debate surrounding his status as ‘a Communist’ speaks as much to his significance as a symbol as it does his personal beliefs.

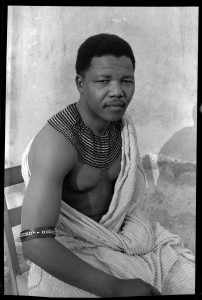

For it is as a symbol that Mandela lived for much of his life, and it is as a symbol that he will continue to live, and is continuing to live, even at the moment of his death. In the first ‘authorized’ biography of Mandela, Fatima Meer wrote of how Mandela had dismissed autobiography as ‘an excuse for an ego trip’, only to request some months later that she begin writing an account of his life. Now, Mandela’s life has become one of the most widely-told tales of human endeavour, documented in written text, in art and in cinema. The construction of Mandela as the symbol of the struggle for South African freedom, which began in the wake of the Soweto Uprising of 1976 and the death of Steve Biko the following year, stands as a parable of the power of image in modern politics, and is probably the most successful example of the imprinting of a single individual as the signifier of a national liberation struggle on a global scale.

It is also the reason why we all appear to ‘own’ our particular sense of the value and significance of Mandela the person. In time, we might wish to interrogate the symbol and revisit the man. But for now, I am happy to simply offer thanks. Hamba Kahle, Mandela.