Dr Grace Huxford is Senior Lecturer in Modern History. She is a social historian of modern Britain, specializing in the Cold War period and with particular interest in the aftermath of the Second World War and the Korean War. She is an oral historian and currently conducting an oral history of British military communities in Germany (1945-2000). She was recently interviewed on BBC Radio 3 about the project as part of a special programme on post-war Germany, coinciding with the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall – you can listen to the interview here. Continue reading

Author Archives: administrator

Forest 404: A Chilling Vision of a Future Without Nature

by Professor Peter Coates , Professor of American and Environmental History, University of Bristol

Binge-watching of boxsets on BBC iPlayer or Netflix is a growing habit. And binge-listening isn’t far behind. Podcast series downloadable through BBC Sounds are all the rage (with a little help from Peter Crouch). Enter Radio 4’s ‘Forest 404’ – hot off the press as a 27-piece boxset on the fourth day of the fourth month. This is something I’ve been involved in recently: an experimental BBC sci-fi podcast that’s a brand-new listening experience because of its three-tiered structure of drama, factual talk and accompanying soundscape (9 x 3 = 27). Continue reading

The Cambridge History of Ireland – Live stream

A panel discussion with the editors to mark the launch of the new Cambridge History of Ireland. The editors Thomas Bartlett, Brendan Smith, Jane Ohlmeyer and James Kelly moderated by Catriona Crowe.

You can watch the Live stream here starting from 13:50 on Monday 30th April.

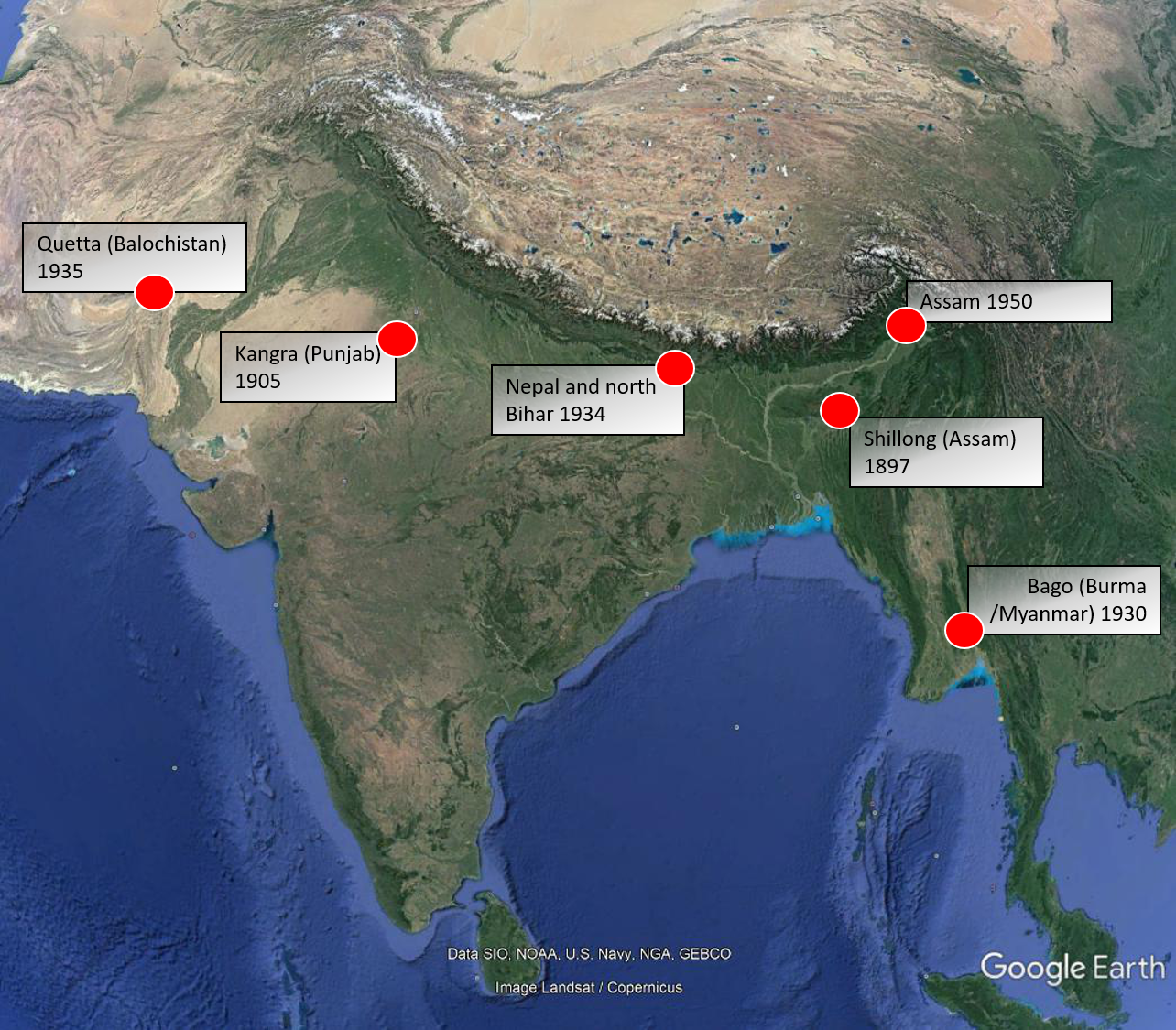

Why are Indian earthquakes missing from history?

Dr Daniel Haines is Senior Lecturer in Environmental History and principal investigator on the project ‘Broken Ground: Earthquakes, Colonialism and Nationalism in South Asia, c. 1900-1960′.

______________________________________________________________________

I first started thinking about earthquake histories because of an accident. It was 2014. I had just started a new job at Bristol, and decided to teach an undergraduate course on natural disasters in South Asia. Looking for ‘good’ disasters to include as case studies, I stumbled across this piece by Roger Bilham about a huge earthquake in Assam in 1897.

The article focused on Tom LaTouche, a British scientist in Kolkata with the colonial Geological Survey of India. The head of the Survey, Richard Oldham, sent him up to Shillong in Assam, near the epicentre, to find out more about the quake. LaTouche wrote extensive letters, to his wife as well as his boss, detailing what he saw.

The letters contained plenty on physical effects, but more intriguing were the incidental references to how people had experienced the earthquake. Usually these were other Brits that LaTouche came across, but sometimes also Indians.

It was clear that the earthquake had been huge, frightening, and calamitous to people across hundreds of square miles.

Why had I never heard of it before?

Over the following couple of years, I dug more into South Asia’s earthquake history, and gradually realised that big, destructive earthquakes are a common occurrence along the Himalayan arc.

The Gorkha earthquake in Nepal in 2015 was a tragically immediate reminder. ‘You must be happy to have a big new disaster in your area, Dan,’ one of my students said shortly afterwards. I wasn’t. But I did notice how vast the media coverage was, even in Bristol, thousands of miles from Nepal. The same was true of other recent South Asian disasters – the 2010 floods in Pakistan, or the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

Earthquakes and other calamities are not just horrible. They are also big news. But where were the historical earthquakes in the literature?

An earthquake that flattened Quetta (now in Pakistan’s Balochistan province) in 1935 also killed roughly 30,000 people. I did my PhD research on the next-door province, Sindh, in the 1930s-1960s. Quetta’s population included numerous Sindhis, and Karachi was the chief destination for refugees evacuated in the weeks after the shaking. Yet I don’t recall coming across any substantial reference to the earthquake, either in primary sources or in history books.

The 1934 Nepal-Bihar earthquake is better known, partly because two of India’s key national figures, Mohandas K. ‘Mahatma’ Gandhi and the Nobel laureate Rabinranath Tagore, disagreed sharply over how to interpret its meaning. Gandhi favoured reading the earthquake as divine punishment for what he termed the sinful practice of untouchability in the Hindu caste system. Tagore preferred a secular approach that focused on natural forces.

Even here, though, the focus has been on the intellectual clash between Gandhi and Tagore’s opposed worldviews. Although leaders and volunteers of the Indian National Congress were instrumental in organising relief and reconstruction in Bihar, only the Indian historian Tirthankar Roy has analysed the earthquake’s broader effects.

My current AHRC-funded research project, Broken Ground, is a partial attempt to correct the record. I’m investigating six earthquakes that shook various parts of colonial and postcolonial South Asia between the 1890s and 1950s, looking at their political, social and environmental ramifications. Such natural disasters are not only a humanitarian issue today, they were also an important part of the experience of colonialism, nationalism, and the post-colonial period for Indians, Pakistanis, Nepalis, Myanmar people and the British alike.

Looking beyond South Asia, earthquakes are surprisingly absent from environmental histories more generally. Historians have tended to focus on other types of hazard: storms, flooding, drought. These disasters usually recur much more frequently than major earthquakes, so it is easier – more satisfying? – to track the changing ways that humans and hazards have impacted on each other over time.

Meanwhile, a handful of historians have looked at the social implications of earthquakes, often with considerable literary and analytical success (find examples here and here). But these works tend to use post-earthquake reconstruction as a prism on local society and politics. The earthquakes themselves can seem more like jumping-off points for general history, rather than historical actors in their own right.

I’ve (just!) discovered Conevery Bolton Valencius’s compelling 2011 book on earthquakes in the early nineteenth century Mississippi Valley. Valencius argues that the earthquakes transformed the middle Mississippi region by turning the St Francis river’s hinterland –which had been a booming trading zone where Cherokees, Osages, Creole boatmen and white American settlers rubbed shoulders – into a swampy marsh. Contemporary American intellectuals wrote extensively about the quakes’ effects on the landscape and its inhabitants, but by the twentieth century this conversation was almost entirely forgotten. The quakes helped drive the region’s diverse population away, but subsequent frontier narratives cast the land as ‘always empty’. History had swallowed the earthquakes.

Perhaps the absence of South Asia’s earthquakes from historical narratives is also due to accidents of geography and timing. Assam’s two earthquakes, in 1897 and 1950, killed relatively few people directly (around 1,500 apiece) and did their worst damage away from the population centres of the plains. The 1905 event, centred on Kangra in today’s Himachal Pradesh, had a much higher death roll (about 20,000) but occurred up in the Himalayan foothills, a region which barely figures in the literature. The three earthquakes of the 1930s, in Bago (Myanmar), Nepal/Bihar and Quetta, coincided with the eventful rise of popular nationalism, the decline of colonial power, the Second World War, and then independence.

By studying all six of the earthquakes together, I hope to tell a coherent story about the changing relationship between the colonial state and its subjects, and between humans and the landscape that these earthquakes dramatically reshaped. Perhaps they were not as central to political changes in late-colonial India as I first thought. But they deserve a more prominent place in the region’s history.

A History of Bristol Reading List

Continuing our series of posts by new staff, Dr Mark Hailwood (Lecturer in History 1400-1700) offers a ‘history of Bristol’ reading list.

Despite growing up just outside the city of Bristol, in nearby Portishead, my knowledge of the city’s history is pretty thin (my excuse is that I’ve always considered myself more of a rural historian). So, when I was appointed to my Lectureship here last summer I quickly took to twitter to canvas for suggestions of good books to fill me in. Now, I haven’t had the chance to read all of these yet, but taking inspiration from the ‘Marooned On An Island Monographs’ series that runs on my own blog, the many-headed monster, I thought I would share the top 5 suggestions that I have narrowed my initial to-read list down to. Of course, my choices reflect my own interests – both chronologically and thematically – so there is a strong early modern and ‘history from below’ flavour to the list.

1) David Harris Sacks, The Widening Gate: Bristol and the Atlantic Economy, 1450-1750 (1991)

The story of Bristol’s transformation from a small medieval commercial city to an entrepot of early modern capitalism is, obviously, an important part of the city’s history – and Harris Sacks’ book is admired for approaching it in a way that identifies the connections between the economic, religious, political, social and cultural developments that made it possible. It’s big, it’s bold, and very much a traditional academic monograph, so it might not be the easiest place to start for uncovering Bristol’s history, but it is regarded as the go-to history of early modern Bristol – even if my colleague Richard Stone’s forthcoming book is set to challenge some of its key arguments (watch this space).

2) Madge Dresser, Slavery Obscured: The Social History of the Slave Trade in an English Provincial Port (2001)

Bristol’s emergence as a major port city was in no small part a consequence of its involvement in the slave trade, and much of the city’s urban growth and built environment were funded by the profits of slavery. Although a number of more recent debates about prominent buildings in the city being named after individuals with strong links to slavery have achieved a high profile, the place of slavery in the city’s history has long been overlooked. But the research efforts of Madge Dresser have done as much as anyone to change that, and this important book provides a detailed account of Bristol’s relationship with slavery that is a must-read for anyone who wants to make an informed engagement with these debates.

3) Steve Poole and Nicholas Rogers, Bristol from Below: Law, Authority and Protest in a Georgian City (2017)

As an unashamed advocate of ‘history from below’ I was very excited to hear about the publication of this book within a few weeks of my arrival in my new post. Poole and Rogers focus on the city’s ‘golden age’ between the Restoration and the riots of 1831, and explore the way that ordinary people contributed to the making of their city – often through conflicts with the mercantile elite that formally governed the city. Riots, protests, class conflict, the lives of ordinary men and women – it’s the kind of classic social history that any social historian wants to read about the place where they live and work.

4) Carl B. Estabrook, Urbane and Rustic England: Cultural Ties and Social Spheres in the Provinces, 1660-1780 (1998).

Although the title doesn’t give it away, this is a book focused on Bristol and its environs. Having grown up in the latter – in Estabrook’s definition the settlements lying within 12 miles of the edge of a major city, in Bristol’s case the area sandwiched between the Cotswolds, Mendips and Severn – I’m interested in this book’s exploration of the relationship between city and countryside in the age of the ‘urban renaissance’. For Estabrook the rural / urban divide ran deep in English culture, and even the inhabitants of rural settlements that sat in the shadow of the big city never felt at ease when they visited it. Hopefully I won’t suffer the same fate…

5) Helen Dunmore, Birdcage Walk (2017)

A bit of a curveball here – this is a work of historical fiction. But these too can help us to connect with the history of our homelands, right? Set during the early 1790s, against the backdrop of a Bristol house-building boom and the fallout of the French Revolution, Lizzie Tredevant negotiates married life and the loss of her radical writer mother. Probably best if I don’t give too much more away, but it is a skilful imagining of life in the Georgian city, and if nothing else there are lots of nice descriptions of walks on Downs in all weathers to inspire you to get out and explore the city for yourself.

If you’ve got your own suggestions of good books on Bristol’s history then please leave a comment below, as I’d love to have them.

A Historian in Antarctica

As the first of a series of blog posts from our new lecturers in 2017/18, Dr Adrian Howkins (Reader in Environmental History) reflects on a Christmas in Antarctica and introduces some of his research interests:

One of the best ways to guarantee a white Christmas is to travel to Antarctica. Over the past few years, while family and friends back home open presents and tuck into roast dinners, I’ve found myself at the bottom of the world conducting fieldwork in a place called the McMurdo Dry Valleys, the largest ice-free region on the Antarctic continent. Winter in the northern hemisphere is summer in the southern hemisphere, and this is the only time of year when it’s really possible to travel to Antarctica. Getting there involves a long flight to Christchurch, New Zealand, and then eight hours on a LC-130 military aeroplane which lands on the sea ice close to McMurdo Station, the largest scientific research station in Antarctica. After several days of safety briefings and orientations, fieldwork begins by flying forty miles in a helicopter out to the McMurdo Dry Valleys, where a handful of small field camps provide accommodation and laboratory space for the scientists studying this unique landscape.

What is a historian doing conducting fieldwork in Antarctica? That is a question I’ve asked myself on more than one occasion, especially when the skies cloud over, the wind picks up, and it starts to feel really cold. The short answer to the question is that since 2011 I’ve been one of a number of principal investigators on the McMurdo Dry Valleys Long Term Ecological Research site, which has been studying the cold-adapted ecosystems of this region for the past twenty-five years. I became involved when the project was looking for someone to integrate some sort of “human dimensions” research into the scientific work of the site. I suggested that in much the same way as the relatively simple ecosystems of the McMurdo Dry Valleys offer interesting opportunities for studying ecological processes, the relatively simple human history of the region offers environmental historians an ideal case study for examining the interactions of human activity, ideas, and the material environment over time, and for integrating this research into the ecological work.

A longer answer to the question of what a historian is doing conducting fieldwork in Antarctica takes me back to my graduate work at the University of Texas where I wrote a doctoral dissertation on the history of a dispute among Britain, Argentina, and Chile over the sovereignty of the Antarctic Peninsula region (on the opposite side of the continent to the McMurdo Dry Valleys). Following an undergraduate degree in modern history at the University of St Andrews in Scotland I’d gone to Texas to study the history of British relations with Latin America, and I came across the dispute in Antarctica as an extension of the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas conflict between Britain and Argentina. While conducting my research, I came to realise how important science and the environment were to the political history of the Antarctica Peninsula region, and I embraced environmental history as an approach that could integrate these different elements. In my first teaching position at Colorado State University I published my dissertation work as Frozen Empires: An Environmental History of the Antarctica Peninsula (Oxford University Press, 2017) and I broadened my research to include the Arctic in a book titled The Polar Regions: An Environmental History (Polity Press, 2016).

This past Antarctic season in the McMurdo Dry Valleys I have been working with soil ecologists on a project to understand the environmental legacy of former field camps. Field camps began to be established in the late 1950s by US and New Zealand teams working in the valleys, and then some have been removed as scientific priorities have changed and environmental awareness has grown. This project began with historical research to collect images and reports that document the location and activities of these camps. We then used historical images to help locate the sites, and then took a series of soil samples in a triangular grid around the most impacted areas. This work involved scooping samples of soil into a plastic whirlpak bag and then taking them bag to the laboratory at McMurdo Station to prepare for biological and chemical analysis. Through a combination of historical and scientific research we hope to learn more about the impact of human activities in the region, which may be useful for managing the environment more effectively into the future.

Alongside my work in Antarctica, I have also developed an interest in the history of parks and protected areas more generally. I have co-edited a collection titled National Parks Beyond the Nation: Global Perspectives on “America’s Best Idea” (University of Oklahoma Press, 2016), which examined how US national park ideas both influenced and were influenced by the experiences of other parts of the world. I’ve worked on a number of projects involving US National Parks, including Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado and Scotts Bluff National Monument in Nebraska. At Rocky Mountain National Park we developed a program called “Parks as Portals to Learning,” which involved taking environmental history students up to the park for a week of intensive study based on the question of how insights from academic history can be incorporated into the practical management challenges of running a park. I’m hoping to be able to develop something similar for students at the University of Bristol over the next few years.

A common theme in much of my recent work has been to ask how environmental history research can help to address some of the social and environmental challenges facing the world in the twenty first century. In Antarctica, for example, it’s difficult to develop effective environmental management strategies without looking at the legacy of past human activities. This concept of “applied environmental history” connects well with the University of Bristol’s strengths in public history, and offers opportunities for reaching out to partners beyond the University, at a variety of different scales. It is an exciting time to be doing environmental history, and I’m very pleased to be at the University of Bristol.

Dr Adrian Howkins.

Blue Planet in historical perspective

Environmental historian Peter Coates is currently working on a project with the Bristol-based BBC Natural History Unit, which is just a five-minute walk from the Department. The recent broadcast on BBC1 of ‘Blue Planet II’ provided the occasion for a number of interviews with the publicity office of the project’s funding body, the Arts and Humanities Research Council. These interviews covered the latest series, its predecessor in 2001, and the work of the project more generally. Environmental history is one of the Department’s distinctive areas for teaching and research.

Colonialism in Shanghai, China’s Global City: Former Bristol PhD student Isabella Jackson on how she wrote her new book

Isabella Jackson describes how her new book emerged from her 2012 PhD thesis here at the department, a process, it sometimes seems, that involves unlearning all the things that had to be learned in order to prepare the thesis. Isabella’s story of presenting her findings on modern Chinese history actually began here in the department 14 October 2002, when as a 1st year undergraduate she gave a seminar presentation on ‘The Chinese World Order and the West’ in my class on the Boxer Uprising in China. After her BA, she took the MA here, then an MPhil in Modern Chinese Studies at Oxford as part of her preparation for the PhD. Robert Bickers

How do we develop our own original line of argument in a research project? And what makes a book from a PhD dissertation? These are two of the biggest questions faced by doctoral students, one early in their research and the other nearer to graduation. When I began my PhD in 2008, I had a one-page outline of a project to investigate how the International Settlement at Shanghai was managed. My supervisor, Professor Robert Bickers, pointed out that while he and one or two others had written about the Shanghai Municipal Council (SMC), a British-dominated colonial body, as part of wider examinations of colonialism in China, no dedicated study of this state-like institution and its long tentacles existed. But another professor in the department warned that institutional history was deadly boring (not quite his words). I knew I needed to provide more than an analysis of how the SMC functioned and how it influenced the city, but I did not know what that might entail.

The Council of 1936-1937, with American, British, Chinese and Japanese members. Image courtesy of Historical Photographs of China, University of Bristol. HPC ref: Bi-s085

So I got reading, noting anything that leapt out as surprising; Professor Rana Mitter, who taught me during my MPhil at Oxford, is a great advocate of paying attention to what is surprising in our research. What kept striking me was the paradox of it being an International Settlement but an expression of British colonialism. How justified was the ‘International’ moniker? I found that as time went by, particularly from the late 1920s, the SMC was increasingly transnational in the members of the council, its staff, and the networks in which those councillors and employees moved. I called this form of colonialism ‘transnational colonialism’. It was still important to demonstrate the huge impact of the SMC on Shanghai, its residents, and the politics of the period, particularly the growth of Chinese nationalism, but I now had a thesis of potentially wider interest to people beyond the field of Shanghai history.

The Shanghai Municipal Archives on the Bund

After a year in the Shanghai Municipal Archives and longer writing up, I completed my PhD in 2012. The next job was to adapt my thesis for publication as a monograph. My PhD examiners made many useful suggestions, and they needed more convincing on aspects of my argument, so I knew the areas that had to be strengthened. A couple of people advised me to leave my thesis for six months and come back to it afresh, when I’d be able to see its strengths and weaknesses more objectively, which I did. I’ll never know whether this was a good plan in my case or not, but in retrospect, I wish I had ploughed straight on with the book rather than breaking my momentum. What prompted me to get back to it was meeting the immensely encouraging Lucy Rhymer, Commissioning Editor for Asian Studies at Cambridge University Press, at a British Association for Chinese Studies conference. She liked the look of my paper and asked if I was publishing my PhD. I promised to send her a proposal that month, and it was just the push I needed to start to see my project as a potential book aimed at a wide range of readers.

A book proposal requires the writer to focus on key words, audience, market, and significance. Summarising each chapter in terms of the claims I was making helped me develop a punchier style. I now needed to locate my work in relation to the existing field in a different way to a dissertation literature review, which shows how a project builds on and departs from the existing scholarship. I had to demonstrate not only that there was a ready market for a book about how precisely colonialism worked in Shanghai, but also that I was taking a different approach to existing books on Shanghai and historical Sino-British relations. As much of that work is by none other than my excellent supervisor, Robert Bickers, this was a delicate task! I related my work to comparable colonial sites, from smaller treaty ports in China and the colony of Hong Kong to municipalities in British India and even Egypt, which was subject to both British and French imperialism.

Lucy asked for sample chapters, so I revised what I thought were my strongest chapters and she sent them out for review. The anonymous readers’ reports provided more guidance as to how to make the manuscript more book-like. By this point I thought I was stressing the significance of my findings a lot, but I needed to do it even more explicitly. Writing my response to the readers was perhaps the most useful stage: much of what I wrote in answer to their critique went into my Introduction, setting out my stall as directly as I could. Next I had to deliver the full manuscript to go back for review, and this time the readers were satisfied, as were the Cambridge Syndicate in turn, and I got the contract for the book. For the first time I had a deadline, and there is nothing like a deadline to get me writing. Three months later I sent off the final manuscript, fully indexed. Every stage since then has been enjoyable: seeing the proofs laid out like a real book, choosing the cover image, and finally receiving my own copies.

The Cambridge University Press Syndicate, which takes the final decision on whether to offer a contract for a book. Source: http://www.cambridge.org/about-us/who-we-are/press-syndicate

The project has come a long way from the one-page outline with which I began my PhD. It remains to be seen how readers will respond to my argument about transnational colonialism in Shanghai, but I am confident that I am making a new contribution to debates that should be taken into account as we seek to understand the different permutations of colonialism in China and beyond.

Avonmouth Docks – some uncharted territory

In this blog, second-year undergraduate History student Jacky Baker reflects on her time spent this summer working in a local archive:

“Archiving is yet another one of those fields that has, to some degree, come out of the closet to understand itself as a form of creation and production imbued with subjectivity rather than an objective bureaucratic practice.”

Marvin Taylor, the Director of Archives at Fales Library

For a week this summer, I was creative, got dirty, and had fun, whilst moving, sorting and categorising about one thousand books, pamphlets, and journals. The end result was a library at the Bristol Port Company in which I hope existing users can relocate items, and new users can go exploring.

Aerial view of Avonmouth and Portbury Docks. Reproduced by kind permission of The Bristol Port Company.

As I was staring at the bookshelves, working out where to start, I was reminded of a recent conversation. The conversation was with David Lane, a writing fellow of Bristol University researching for a new play, who made me think that an archive could be alive. The objects, books and letters of the past remain a forgotten store until retrieved. In the role of creator of the library/archive this summer, it was my responsibility to create a manual, map, or phrase book for present-day historians to explore the past and find answers, or more questions.

The library did take on a life for me. I certainly talked to some of the books, when they failed to stand up, or when a gap on the shelf was too small for a category of publications planned for it. Tetris – an older computer game – became a reality for me, that week.

I was first introduced to the Bristol Port Company archives on a research visit, for my first year undergraduate project on the 1949 Dock Strike, as part of Dr Grace Huxford’s unit ‘Britain’s Cold War’. The majority of records relating to the Port of Bristol before 1991, when it was purchased from Bristol City Council, lie in the city’s archives. However, I found gaps where I expected to find original source material. With an email, and an appointment made, I was introduced to the Bristol Port Company and their reference library which certainly helped my project. I resolved then, to seek a revisit, and try to discover more items on shelves, and / or in boxes on the floor at Avonmouth.

One could call it work experience, as I had volunteered to look at the Port’s forgotten resource. Businesses, needing to focus on the present and the future, have little time to spare for such a task. Fortunately for me John Chaplin, the Director of External Affairs and Special Projects, very trustingly giving me free reign as I set off exploring.

Whilst considering if Bevin’s biography belonged with ‘Trade Union and Industrial Relations’ or ‘History and Art’, I wondered how many other local companies have areas such as this: a room of books, or a dark cupboard of dusty old ledgers forgotten by many, sometimes read by a few whilst perhaps killing a wet lunchtime. Could a keen amateur offer their services to other companies to bring some order, or at least make the archives more accessible for other historians to use?

After five days. I had categorised the library and tried to create a framework for later completion with a more detailed book list. Some items I listed individually, to show others the dormant source material located on their shelves. For example, one envelope contained a velum pilotage certificate, and letters of reference for an Arthur Jackson, from the 1920s. One book – the personal telephone directory of the Traffic Manager, from the 1950s – was an analogue ‘Facebook’ containing clippings of marriages, deaths, and promotions of those contacts in his directory. There was an insurance ledger dating back to the 1890s, and minutes of the Dues Committee, from around the same time, that had extracts of letters protesting at the rate of charges for harbour use. Should another undergraduate take up the study of the Canadian Seamen’s Union 1949 Dock strike, they could find the Rochdale Report, printed TGWU leaflets warning about Communist influence, and other interesting references to the Cold War period.

The end result was something I felt proud to have created. The library, though already in existence, had a frame of categories. Even the Chairman, Terence Morduant, expressed an interest in spending an afternoon amongst the books, reacquainting himself with old friends, and finding some new ones. Next year I will doing some more archive exploring, this time in the engineers’ library at The Bristol Port Company, hard hat not required (I hope).

The White House, Unguarded Gates, and the Huddled Masses

As President Trump endorses a bill to restrict immigration, Lecturer in North American History, Julio Decker, reflects on the history of US attitudes to the ‘huddled masses’.

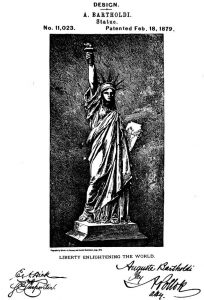

Much of what has been happening since the American election last year seems novel and unprecedented. It seems difficult to remember a single week of the Trump administration that did not collide with political customs. Last week, another seemingly unprecedented break with the past happened when White House Aid Stephen Miller declared that Emma Lazarus’s poem ‘The New Colossus’, engraved in the pedestal, was irrelevant as it was added after the Statue of Liberty had been erected. In a heated exchange with CNN’s Jim Acosta, he defended President Trump’s support for a Senate Bill that would halve the number of legal immigrants allowed to come to the United States. The bill would test potential migrants’ job prospects before admission, among them their English-language skills.

For many commentators, this seemed like a new low: denigrating a poem that stood for the American tradition of calling for the world to send ‘your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free’. And there is a case to make that Miller misrepresented the poem, which was written as part of a fundraiser for the statue, thus being explicitly connected to the Lady of Liberty. But Miller did get one thing right: opposition to immigration, and to the poem and what it represented, was not a break in American history: it had existed even before 1903 when the plaque with the poem was installed. Just like the travel ban, the Trump administration’s immigration policy proposals have such a clout because the restrictionist impulses have a long tradition in American history.

Lazarus wrote the sonnet in 1883, one year after Congress had passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned – with only a few exceptions – an entire nationality from entering the United States. Opposition to immigration was not limited to those from Asia: when the origin of most new arrivals started to shift from North-western to South-eastern Europe in the 1880s, many Americans started to demand restriction. These nativist voices explicitly rejected the spirit embodied in ‘The New Colossus’ – new immigrants were depicted as lowering wage levels, being unwilling to assimilate, and lacking the cultural knowledge to participate in a democratic society. In the late nineteenth century, these views were framed in contemporary racial theories – new immigrants were classified as part of the Alpine or Mediterranean races, supposedly inferior to Anglo-Saxons.

From the 1890s, nativist voices began to be heard in Washington. Conservative think-tanks and lobby groups such as the Immigration Restriction League built alliances with farmers, Southerners, and labour unions. Influential Senators such as Henry Cabot Lodge started to lobby for new means of reducing immigration. What university degrees, skills, job prospects, and language skills are to conservative lawmakers today, the literacy test was for nativist reformers of the early twentieth century. At Ellis Island and at other inspection sites at American borders, immigrants were meant to prove that they could read and write. Restrictionists argued that the test was impartial, and that apart from testing a crucial skill for participation in American politics, it would also exclude the most undesirable, as illiteracy supposedly correlated with criminality, poverty, and dependence on state aid. The real motivation, however, was another correlation – that illiteracy was the lowest among people from North-western Europe. Depending on the audience, restrictionists would openly address this racial dimension– the founder of the Immigration Restriction League, Prescott F. Hall, declared in 1919 that immigration restriction should be seen as a method of keeping ‘inferior stocks’ from ‘both diluting and supplanting good stocks’.

Henry Cabot Lodge. Image by John Singer Sargent – National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Public Domain.

For most of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, however, Presidents rejected the ‘radical departure from our national policy’, as Grover Cleveland wrote when he vetoed a literacy test bill in 1897. Woodrow Wilson vetoed similar bills in 1913 and 1915. Furious with the President’s threat of a veto, Senator Lodge declared that instead of clinging to the tradition embodied by ‘The New Colossus’, he should read Thomas Bailey Aldrich. In 1893, this poet had written ‘The Unguarded Gates’ as a reply to Lazarus, bemoaning that the nation let in ‘featureless figures of the Hoang-Ho, Malayan, Scythian, Teuton, Kelt and Slave’, who brought ‘with them unknown gods and rites’. The poem called out to Lady Liberty to rethink her welcome to the world:

In street and alley what strange tongues are loud,

Accents of menace alien to our air,

Voices that once the Tower of Babel knew!

O Liberty, white Goddess! Is it well

To leave the gates unguarded?

Lodge was not the first to bring Aldrich’s poem into political debate – it was popular among restrictionists. While citing it did not convince Wilson in 1913, the nativists’ lobby work did eventually pay off when the United States entered World War One. Public doubts over immigrants’ loyalties helped restrictionists to organize the Congressional votes necessary for overriding another veto by Wilson. In 1917, the new Immigration Act included the literacy test. It also banned all immigration from the so-called Asiatic Barred Zone, stretching from the Ottoman Empire to New Guinea. While this wholesale ban excluded migrants regarded as non-white, the literacy test proved to be less effective than originally envisioned. In the 1920s, a wide coalition of Democrats and Republicans passed acts establishing a quota system which drastically limited immigration from South-eastern Europe. Like today, the radical anti-immigrant rhetoric was supported by the White House. ‘American liberty’, vice-president Calvin Coolidge wrote in an article for Good Housekeeping in 1921, ‘is dependent on quality in citizenship’. While the ‘Nordics propagate themselves successfully’, he wrote, in the question of limiting immigration ‘racial considerations [are] too grave to be brushed aside’. It is only ‘when the alien adds vigor to our stock that he is wanted’ – to ensure national progress, racially inferior immigrants therefore had to be excluded, he argued.

Symbols like the Statue of Liberty are imbued with political meaning. For many liberal Americans, the statue stands for an American tradition of welcoming immigrants regardless of English-language skills, race, or ethnicity. But the statue so many immigrants saw on their arrival to New York also embodies another powerful strand in American politics, one those with a positive view of the United States tend to repress. Immigration legislation was also shaped by a strong tradition of nativism, racism, and conservatism, one that politicians can mobilize when calling for tighter regulation. In their vision of American history, Lady Liberty was wrong in welcoming the world’s poor and huddled masses – this is why ultra-nationalists interpret the latest Vogue cover as a criticism of the Trump administration. Understanding this history gives us a stern warning: when this tradition is embraced by the White House, consequences for immigrants can be dire.