Andrew Hillier – who recently completed a PhD at the University of Bristol – shares his research in this blog, which addresses the history of Malaysian diaspora by exploring its spaces, places, furnishings and memorials.

Walter and Betty Medhurst arrived in Melaka (Malacca) in 1817. A printer by trade, Walter had been sent by the London Missionary Society (LMS) to the Ultra-Ganges region, to assist Robert Morrison and William Milne in the task of printing and distributing translations of the Bible and other tracts. But Medhurst was fired with evangelical zeal and his principal aim was to become a missionary himself. Two years after his arrival, having acquired a reasonable command of Chinese and shown a fervent devotion to the Gospel, he was ordained and spent a further two years in Malacca before moving to Penang. His fervour did not always endear him to his colleagues and as a result, a year later, he was transferred to Batavia (present-day Jakarta), where he lived for the next twenty years. The objective was to enter China and begin the mass ‘conversion of the heathen’ and so, when the first treaty ports were opened in 1843, Medhurst immediately embarked on this task.

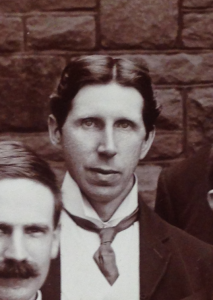

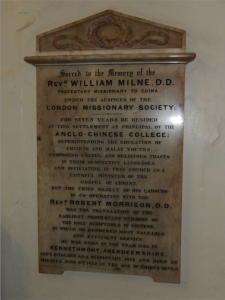

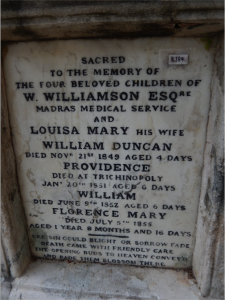

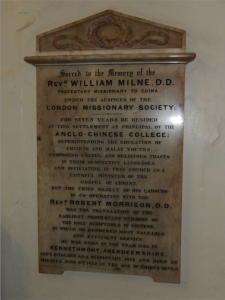

As the first of my forbears to ‘go east’, the Medhursts are the starting point for my thesis, in which I explore the relationship between family and empire through the lens of four generations, who lived and worked in east and south-east Asia. Although they only spent four years in Malaysia, this was a formative time for Walter and Betty and, whilst Medhurst wrote of his experiences in China: Its State and Prospects (1838), I wanted to see the places for myself. In the event, apart from a fine memorial to William Milne in the Dutch Church in Malacca (plate 1), I found little evidence of the LMS, since, after the opening of the treaty ports, it removed its operations to Hong Kong.

However, the visit proved rewarding because there is a lively interest in the history of both Malacca and George Town (as Penang’s port-city is still called), spear-headed by Khoo Salma Nasution, who also runs her own publishing house. This contributed to the two port-cities being jointly listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites in July 2008. In the words of the Declaration, their rich multi-cultural heritage had been preserved and maintained over several centuries and could still be seen in their ‘…unique architecture, culture and townscapes’. Of this, three elements were of particular interest.

1. Memorial tablet to William Milne, Dutch Church, Malacca.

First, the vibrant plural society of Chinese, Malay and Indian, which greeted Medhurst on his arrival, can still be found in both the buildings and the everyday life. Secondly, whereas Britain was the only European power to colonise Penang, in Malacca, the presence of the Portuguese and, later, the Dutch had plainly influenced the port-city’s development. Thirdly, leaving aside the European presence, what had given rise to the plural society in both settlements was the mass migration, principally of Chinese but also of Indians, Indonesians and others, which had begun in the 1500s. Accordingly, by the early 1800s, within the framework of Britain’s formal empire, there was an informal empire or diaspora, promoted by the Chinese both economically and culturally. Moreover, family had played a key role in stimulating and consolidating this process.

To understand this, it is logical to begin with Malacca because it was there that the Portuguese first landed in 1511, and established a safe haven for their voyages to and from the Spice Islands. Whilst there is little tangible evidence of this now, by inter-marrying, they added to the island’s plural society and left an enduring Catholic legacy. When the Dutch arrived, they introduced a very different version of Christianity and European culture, which shaped the city’s development during the seventeenth and eighteenth century. By the time the British formally acquired the Settlement in exchange for Bencoolen in 1824, the port had lost its importance, with Penang providing better facilities and Singapore already becoming a busy entrepôt. As a result, it is the Dutch influence which continues to exemplify the European presence.

It is evident in the simple lines of the Dutch Reformed Church which overlooks the central square, in the administrative buildings, such as the Stadthuys, and in the street architecture, where the Dutch style of merchant house, locally known as a ‘shophouse’ was introduced. A typical example can be found in Heeren Street, adjoining Jonkers Street. Totally derelict twenty years ago, it has been carefully restored by the Heritage of Malaysia Trust. It illustrates how Dutch building methods and materials were used in the construction of such houses and how, later, it served the needs of a Chinese merchant and his family. The shop’s façade contains one large shutter which would fold down to serve as a counter for displaying wares (plate 2).

2. Facade of restored shop-house, Heeren Street, Malacca, 2016.

Inside, there is a central open courtyard, with the family rooms being at the rear (plate 3). On the bench are examples of the original Dutch bricks which were shipped as ballast and then used for building. Fittingly, inside, there is a Vermeer print to show how closely the design matches that of similar houses in Delft. Here, therefore, we have strong linkages between Dutch and local Malaysian society.

3. The Inside courtyard of the shop-house

About 50 metres down the same street is a strikingly different building – one built by a rich Peranakan Chinese, or as they are more usually called now, a baba-nyonya. These were the Chinese who, from the 1500s, came over to settle and, often leaving a wife at ‘home’ on the mainland, to whom they would return from time to time, married a ‘local’ woman, either Malay or Indonesian. Contrary to Western colonial culture, where such inter-marriage was frowned upon, this class became respected and often affluent and formed a key part of the local community.

This is all brought together in the baba & nyonya Heritage Museum, the former home of a baba, Chan Cheng Siew (1865-1919), whose father had first migrated from China and who, having made a fortune in rubber and other investments, built this lavish mansion for himself and his family (plate 4).

4. The Former Home of a Rich Peranakan, Malacca.

Whilst it is Chinese in its overall appearance and much of its furnishings, with chairs and tables made of Chinese black-wood and decorated with mother-of-pearl inlay, the fashion was to import and use British materials: plasterwork, tiles from Stoke on Trent, wrought iron pillars and beams manufactured by Macfarlanes in Glasgow and art nouveau glass for windows, chandeliers and artefacts (plates 5).

5 5. Eclectic Peranakan Style importing British influences.

5 5. Eclectic Peranakan Style importing British influences.

Further down the same street is Hotel Puri, the ancestral home of Tan Kim Seng, a third generation Chinese, born in Malacca, whose grandfather, like many others, first came from the Eng Choon district of Fujian in the eighteenth century. The current house, which was built in 1876, retains many of the original Chinese features as well as a library where the story of the Tan dynasty is displayed. By chance, I got talking to a cleaning lady who told me the history of her family, which was Indian, third generation Malay. Taking me to a map, she described the trajectory of their lives which now extended to Singapore, Italy, Britain and Canada, which she still visited. Thus, Malacca’s plural culture, underpinned by family connection, continues to thrive.

A similar pattern can be found in Penang where, in the nineteenth century, wealthy Chinese and Peranakan families established themselves, living and working alongside the British. It is illustrated by two houses, previously derelict but which have been restored by entrepreneurs dedicated to preserving Penang’s heritage. The Blue Mansion was built by one of Penang’s richest merchants, Cheong Fatt Tze, who arrived penniless from Guangdong in the mid-nineteenth century, and went on to amass a fortune through rubber, coffee and tea investments, and was appointed Consul-General to the Qing government in the 1890s. The house comprises 38 rooms, 5 courtyards and seven staircases and is a typical mixture of Chinese and European taste. One of its most distinctive features is the ‘cut and paste shard’ porcelain decoration on the outside of the building, the restoration of which could only be done by craftsmen brought over from the People’s Republic of China. Cheong left eight wives and six sons but none of them were able to continue his legacy.

The Pinang Peranakan Mansion was owned by a very different type of Straits Chinese. Chung Keng Kwee made his fortune through tin mining and other more dubious enterprises and was one of the principal leaders of the Chinese secret societies, until they were outlawed in the 1880s. Born in 1821, Chung came from a family of farmers living in a remote Hakka village in the region of Zengcheng, east of Guangzhou. Coming to the mainland in search of his father, he quickly established himself as an astute businessman and was appointed leader of one of the secret societies. Frequently in dispute with other Chinese Clans, the rivalries culminated in the Larut Wars which indirectly led to the Pangkor Treaty (1874) and the introduction of a British Resident as ‘adviser’ to the Sultan. Whilst the house has been restored to reflect this family history, the contents are primarily Peranakan, albeit it is difficult to define that style precisely.

The importance of family in these processes is exemplified in the ancestral home of the Khoo Clan, Leong San Tong Khoo Kongsi. The Khoo family originated from Sin Kang Village in Fujian and was one of the Five Big Clans that formed the backbone of the Hokkien community in early Penang. According to the Kongsi curator, Lawrence Cheah, the birth of the first Khoo clansman in Penang took place in 1775. His son married a local woman and their children were thus baba nyonya. The earliest Khoo clansmen to Penang earned their livelihoods as fishermen and small-time merchants but, when Francis Light established the port-city in 1786, the Clan began to build their fortune, bringing over from China not only their own kinsmen but also substantial contingents of Chinese labour.

6. The Khoo Ancestral Temple, Penang

In 1850 the Clan bought the land on which their home now stands, presided over by its giant ancestral temple. In the adjoining rooms, the Clan’s history is displayed, with memorial tablets recording its members’ achievements, amongst whom are a number of UOB alumni (plate 7).

7. Bristol Alumni, Khoo Temple.

Each year, coming from all over East and South-east Asia and further afield, the Clan assembles at the Kongsi and nowhere could better represent the importance which the Chinese still attach to ancestral worship and filial piety than this set of magnificent buildings.

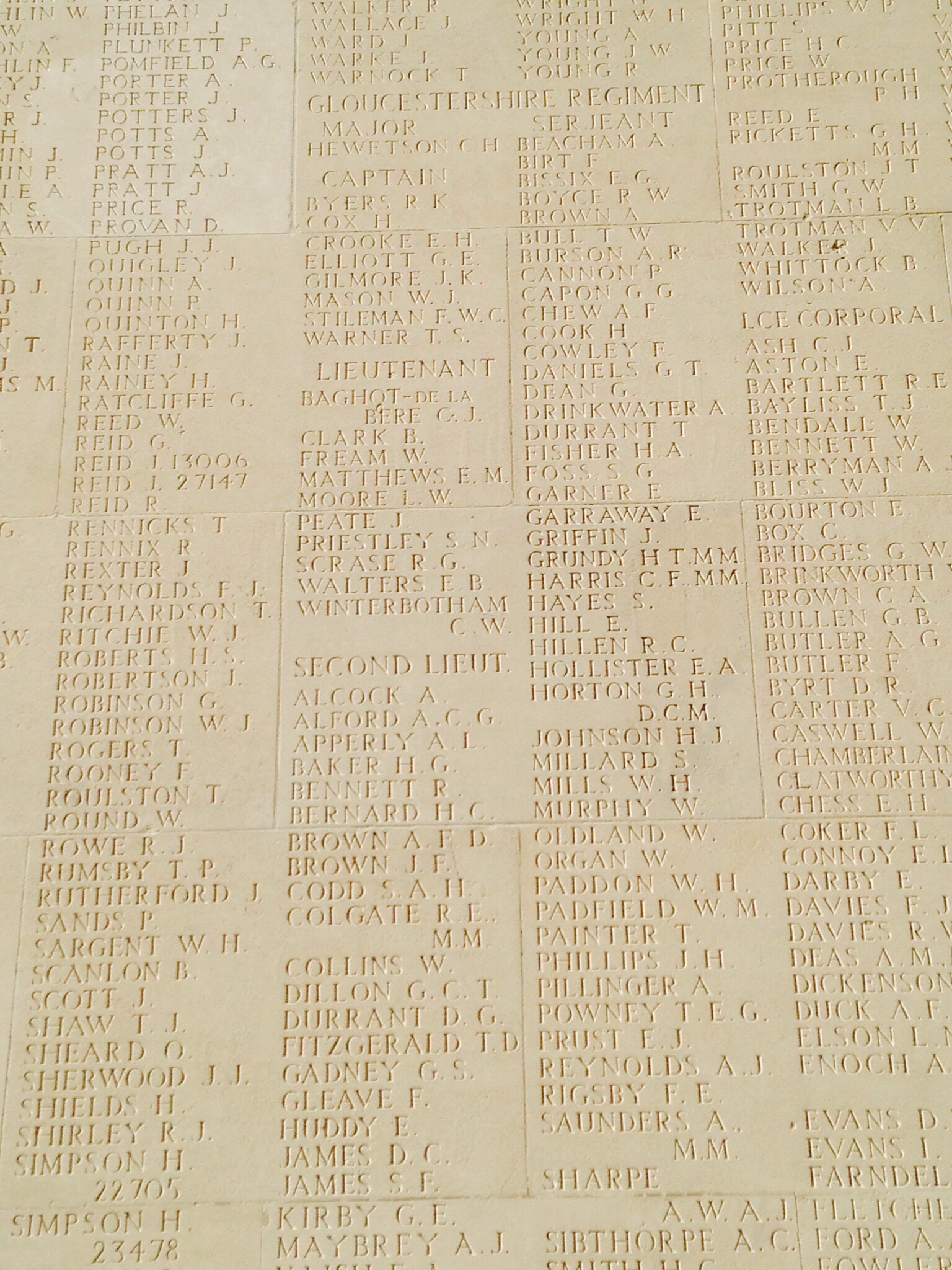

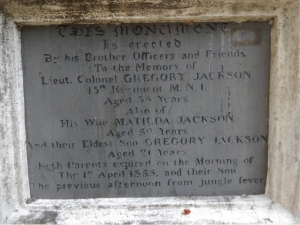

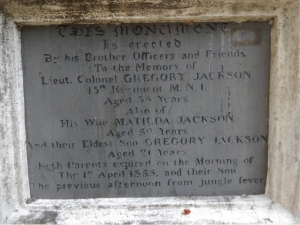

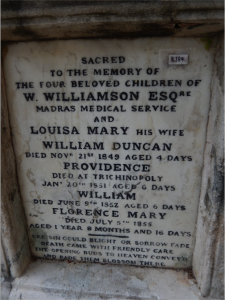

Whilst the formal British presence is represented by standard colonial architecture – Fort Cornwallis, former government buildings and a number of churches – the everyday life can be found in the street architecture and arcades, and, of course, in the Christian Cemetery. In this tranquil, if somewhat unkempt, setting, the hazards and heartache of colonial life can be found inscribed on gravestones and memorials. The following provide a few poignant examples.

8. Tombstones, Christian Cemetery, George Town.

Considering these lives in the context of this society, two questions occurred to me. First, what sort of contact took place between the British and this affluent Chinese/ Peranakan community? That there was a degree of intellectual interaction is evident from the Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, produced and edited by James Logan between 1847 and 1858, and the proceedings of various learned societies – see Su Lin Lewis, ‘Between Orientalism and Nationalism: The Learned Society and the Making of “South East Asia”’, 10 (2013) Modern Intellectual History, pp. 353-374. But it would be interesting to know how this developed when imperialism became more strident. Secondly, given the appetite for British materials and furnishings, how was the exercise of designing, ordering and shipping from Britain performed? Might there be private archives with records of such transactions and what would they tell us about these relationships? Given the number of UOB alumni, perhaps there is scope for forging linkages between the University and Penang to explore these sort of questions.