Dr Daniel Haines is Senior Lecturer in Environmental History and principal investigator on the project ‘Broken Ground: Earthquakes, Colonialism and Nationalism in South Asia, c. 1900-1960′.

______________________________________________________________________

I first started thinking about earthquake histories because of an accident. It was 2014. I had just started a new job at Bristol, and decided to teach an undergraduate course on natural disasters in South Asia. Looking for ‘good’ disasters to include as case studies, I stumbled across this piece by Roger Bilham about a huge earthquake in Assam in 1897.

The article focused on Tom LaTouche, a British scientist in Kolkata with the colonial Geological Survey of India. The head of the Survey, Richard Oldham, sent him up to Shillong in Assam, near the epicentre, to find out more about the quake. LaTouche wrote extensive letters, to his wife as well as his boss, detailing what he saw.

The letters contained plenty on physical effects, but more intriguing were the incidental references to how people had experienced the earthquake. Usually these were other Brits that LaTouche came across, but sometimes also Indians.

It was clear that the earthquake had been huge, frightening, and calamitous to people across hundreds of square miles.

Why had I never heard of it before?

Over the following couple of years, I dug more into South Asia’s earthquake history, and gradually realised that big, destructive earthquakes are a common occurrence along the Himalayan arc.

The Gorkha earthquake in Nepal in 2015 was a tragically immediate reminder. ‘You must be happy to have a big new disaster in your area, Dan,’ one of my students said shortly afterwards. I wasn’t. But I did notice how vast the media coverage was, even in Bristol, thousands of miles from Nepal. The same was true of other recent South Asian disasters – the 2010 floods in Pakistan, or the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

Earthquakes and other calamities are not just horrible. They are also big news. But where were the historical earthquakes in the literature?

An earthquake that flattened Quetta (now in Pakistan’s Balochistan province) in 1935 also killed roughly 30,000 people. I did my PhD research on the next-door province, Sindh, in the 1930s-1960s. Quetta’s population included numerous Sindhis, and Karachi was the chief destination for refugees evacuated in the weeks after the shaking. Yet I don’t recall coming across any substantial reference to the earthquake, either in primary sources or in history books.

The 1934 Nepal-Bihar earthquake is better known, partly because two of India’s key national figures, Mohandas K. ‘Mahatma’ Gandhi and the Nobel laureate Rabinranath Tagore, disagreed sharply over how to interpret its meaning. Gandhi favoured reading the earthquake as divine punishment for what he termed the sinful practice of untouchability in the Hindu caste system. Tagore preferred a secular approach that focused on natural forces.

Even here, though, the focus has been on the intellectual clash between Gandhi and Tagore’s opposed worldviews. Although leaders and volunteers of the Indian National Congress were instrumental in organising relief and reconstruction in Bihar, only the Indian historian Tirthankar Roy has analysed the earthquake’s broader effects.

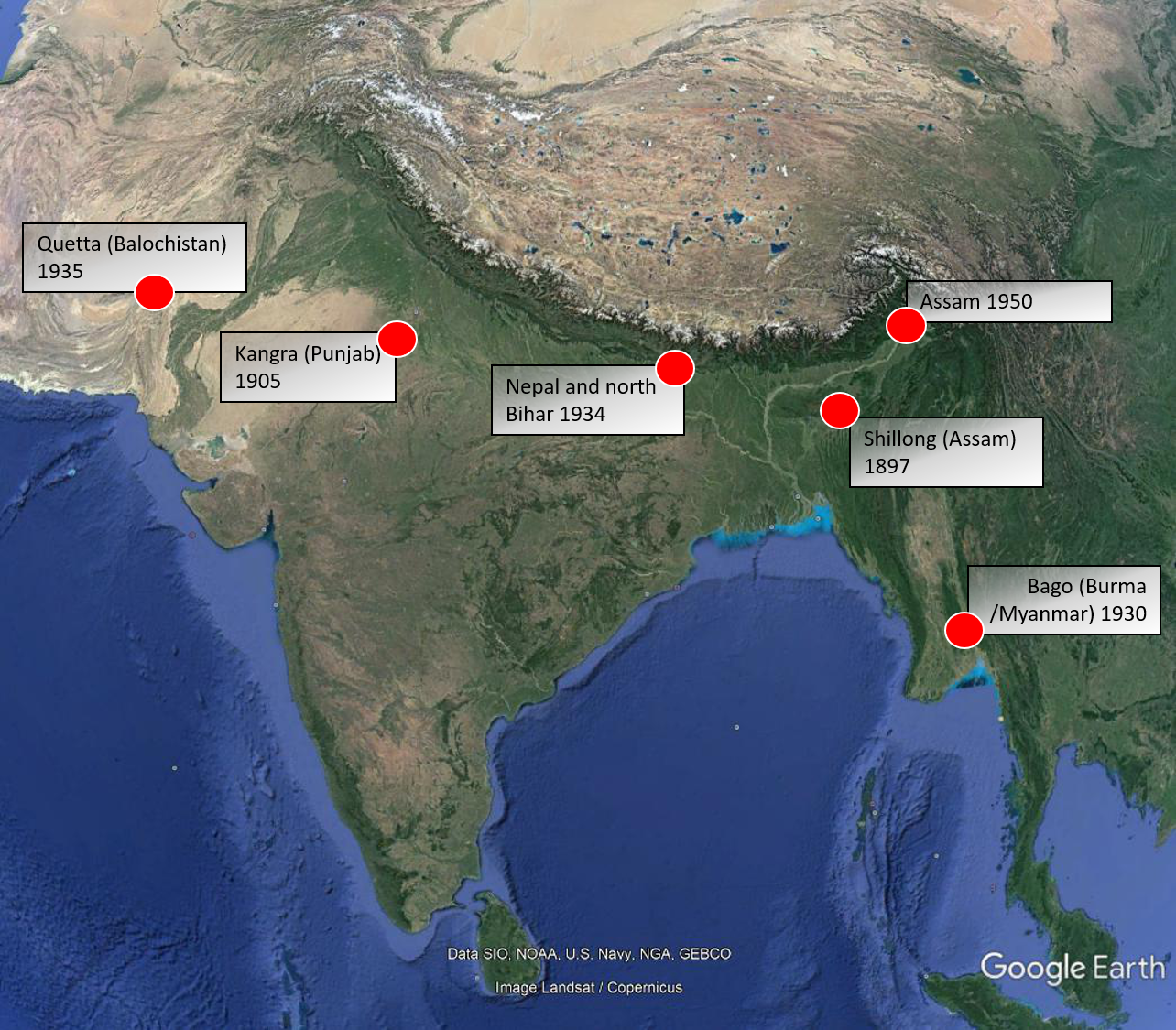

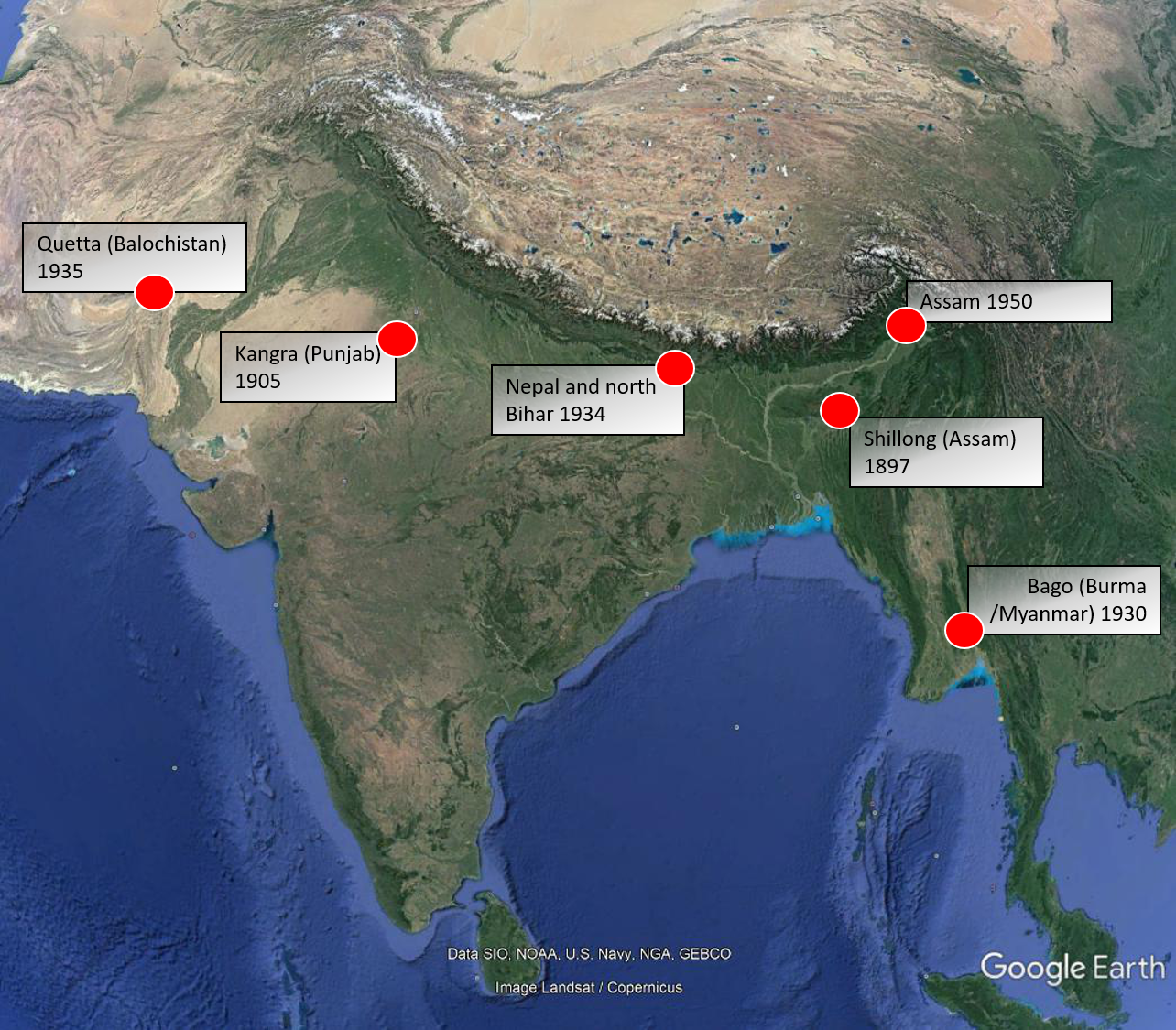

My current AHRC-funded research project, Broken Ground, is a partial attempt to correct the record. I’m investigating six earthquakes that shook various parts of colonial and postcolonial South Asia between the 1890s and 1950s, looking at their political, social and environmental ramifications. Such natural disasters are not only a humanitarian issue today, they were also an important part of the experience of colonialism, nationalism, and the post-colonial period for Indians, Pakistanis, Nepalis, Myanmar people and the British alike.

Looking beyond South Asia, earthquakes are surprisingly absent from environmental histories more generally. Historians have tended to focus on other types of hazard: storms, flooding, drought. These disasters usually recur much more frequently than major earthquakes, so it is easier – more satisfying? – to track the changing ways that humans and hazards have impacted on each other over time.

Meanwhile, a handful of historians have looked at the social implications of earthquakes, often with considerable literary and analytical success (find examples here and here). But these works tend to use post-earthquake reconstruction as a prism on local society and politics. The earthquakes themselves can seem more like jumping-off points for general history, rather than historical actors in their own right.

I’ve (just!) discovered Conevery Bolton Valencius’s compelling 2011 book on earthquakes in the early nineteenth century Mississippi Valley. Valencius argues that the earthquakes transformed the middle Mississippi region by turning the St Francis river’s hinterland –which had been a booming trading zone where Cherokees, Osages, Creole boatmen and white American settlers rubbed shoulders – into a swampy marsh. Contemporary American intellectuals wrote extensively about the quakes’ effects on the landscape and its inhabitants, but by the twentieth century this conversation was almost entirely forgotten. The quakes helped drive the region’s diverse population away, but subsequent frontier narratives cast the land as ‘always empty’. History had swallowed the earthquakes.

Perhaps the absence of South Asia’s earthquakes from historical narratives is also due to accidents of geography and timing. Assam’s two earthquakes, in 1897 and 1950, killed relatively few people directly (around 1,500 apiece) and did their worst damage away from the population centres of the plains. The 1905 event, centred on Kangra in today’s Himachal Pradesh, had a much higher death roll (about 20,000) but occurred up in the Himalayan foothills, a region which barely figures in the literature. The three earthquakes of the 1930s, in Bago (Myanmar), Nepal/Bihar and Quetta, coincided with the eventful rise of popular nationalism, the decline of colonial power, the Second World War, and then independence.

By studying all six of the earthquakes together, I hope to tell a coherent story about the changing relationship between the colonial state and its subjects, and between humans and the landscape that these earthquakes dramatically reshaped. Perhaps they were not as central to political changes in late-colonial India as I first thought. But they deserve a more prominent place in the region’s history.