In this blog post, Professor Kate Skinner reflects on a book she read this summer – Women Talking – and draws connections to her current research in gender and legal history.

Content warning: This post contains descriptions of rape and sexual and gender-based violence.

TLDR 1: The law matters in dealing with sexual and gender-based violence.

TLDR 2: If you don’t want to read the book, you can watch the film instead.

Early this summer, I read Women Talking by Miriam Toews (Faber & Faber, 2018). The story revolves around an imaginary debate between women in a Mennonite settlement in the aftermath of a shocking discovery: a group of eight men within their small, agricultural, religious community had repeatedly sprayed powerful animal tranquiliser over women and girls as they slept and raped them in their ensuing stupor.

Over a period of four years, the women and girls in the story had awoken with painful injuries and fragments of disturbing dreams. They were repeatedly told by the community’s male elders that this was the work of demons upon their wild female imaginations, until one woman stayed awake long enough to catch a perpetrator climbing through her window in the dead of night, animal tranquiliser in hand. The police had been called, and the rapists taken into custody. The women then learn that the elders are selling off assets to raise bail money so they can bring the men home and effect a ‘reconciliation’ with their victims. The women must decide what to do.

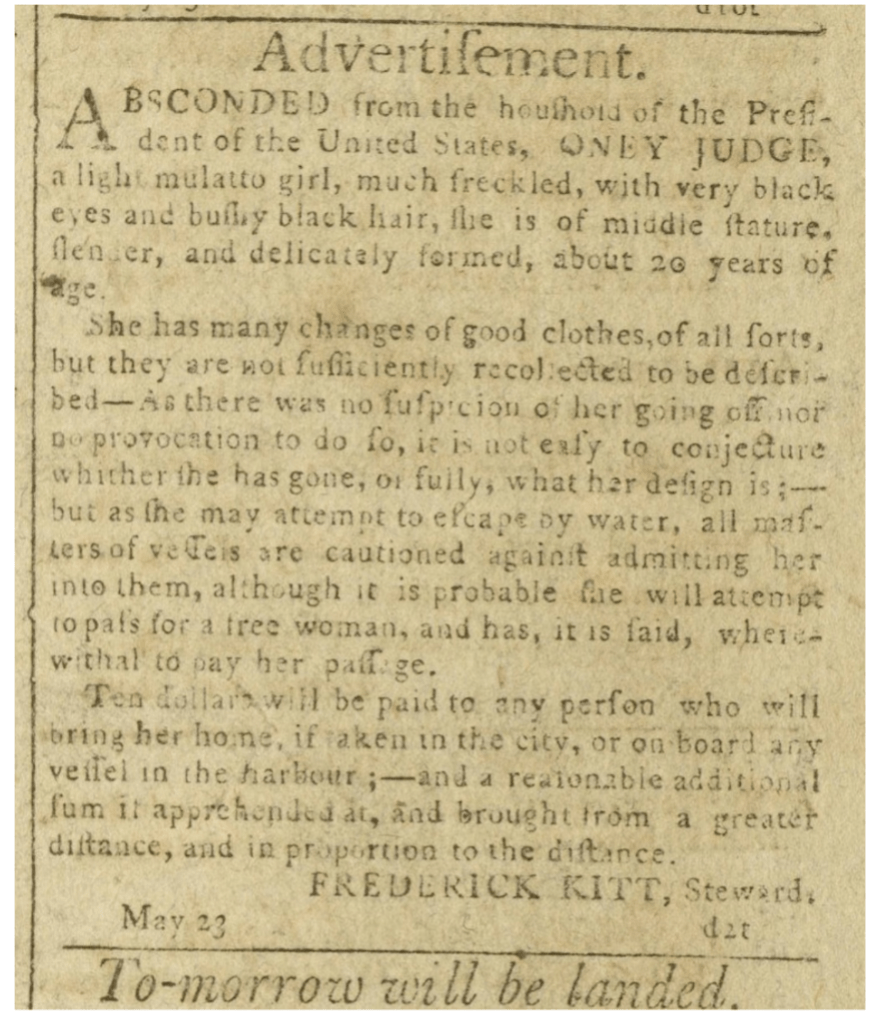

The story is narrated by August Epp, a schoolteacher. Born into the same community, to parents who were ex-communicated and left, Epp had attempted to live abroad for a while. He had been uneasily reaccepted after these unsuccessful acts of rebellion, for the community emphasised that Mennonites should marry other Mennonites, remain in their communities, and limit their contact with the rest of the world. When such contact had to be made, it was mediated by male elders. Herein lay a crucial element of their power.

Epp’s school was for boys only. Most of the women in the story could not write, but they wanted their reasoning and their decisions to be recorded, so they asked Epp to join them at their meetings in a hayloft. There, he writes down the arguments that the women made in relation to three options: ‘Do Nothing’, ‘Stay and Fight’, and ‘Leave’. The arguments, often religious and articulated through agricultural metaphors, are interwoven with glimpses of individual characters, whose experiences shape their perspectives upon Mennonite values, and how those values might be interpreted or adapted to respond to this desperate situation.

The reader thus encounters Salome, who had attacked one of the perpetrators with a scythe upon realising what they had done. It was this action that led the male elders to call the police to the community: the perpetrators were deemed in need of protection from the women’s rage. We also meet Miep, Salome’s three-year-old daughter, who needs medical treatment for infection and injuries sustained through rape. We meet Nettie, who refuses to speak to adults but takes care of children, and Greta, whose teeth were knocked out by her night-time attacker when she momentarily regained consciousness and tried to scream. The women in the story write a manifesto to guide their future lives and depart from the settlement.

The dialogue in Women Talking was imagined, but it was crafted in response to events that were real. They occurred between 2005 and 2009 in Manitoba Colony, a Mennonite settlement in Bolivia. The perpetrators were ultimately convicted and sentenced to prison terms.

Later in the summer of 2024, I was reminded of this story upon seeing a BBC headline: ‘Woman describes horror of learning husband drugged her so others could rape her.’ In this case, a French woman, Gisèle, was repeatedly drugged by her husband, Dominique Pélicot, over approximately a decade. He invited dozens of men into her home whilst she slept and photographed and filmed them as they raped her.

The use of tranquiliser to facilitate repeated rape was a common feature of the two stories, as was the violation of a woman’s privacy, dignity, and bodily autonomy by the perpetrators of this grotesque violence. There were of course many differences. One of them was in how perpetrators were caught.

In the more recent French case, Dominique Pélicot was reported by a stranger for ‘upskirting’ (taking photos up women’s skirts without their consent). This is a criminal offence in France. Once he had been reported, he became the subject of a police investigation. The police thereby gained access to his computer equipment, and images and videos of multiple rapes were discovered.

The law alone cannot prevent many forms of sexual and gender-based violence. The law is a limited tool with which to address the structural causes of this violence. Laws may be robustly or poorly written, and effectively or inadequately applied by police, prosecutors, and judges who are trained, committed, and resourced to varying degrees.

But the law definitely matters. Laws that criminalise actions such as ‘upskirting’ – and indeed the production and circulation of ‘deepfakes’ – are laws that criminalise the violation of privacy, dignity, and bodily autonomy. Without them, the police have fewer  tools with which to investigate the online worlds in which perpetrators of sexual violence increasingly operate.

tools with which to investigate the online worlds in which perpetrators of sexual violence increasingly operate.

Kate Skinner is currently researching in the field of gender and legal history.

Women Talking has since been made into a film.