Sarah Jones is Lecturer in Modern British History. She is a social and cultural historian, and most of her work looks at themes around gender, sexuality, and the history of science and medicine in the 19th and 20th centuries. Her current research looks really closely at print culture, thinking about how the public engaged with scientific ideas about sex through magazines, advice texts, and the news.

What’s the title of your new article, and what’s it about?

My latest article is ‘Science, Sexual Difference, and the Making of Modern Marriages, 1920-1940.’

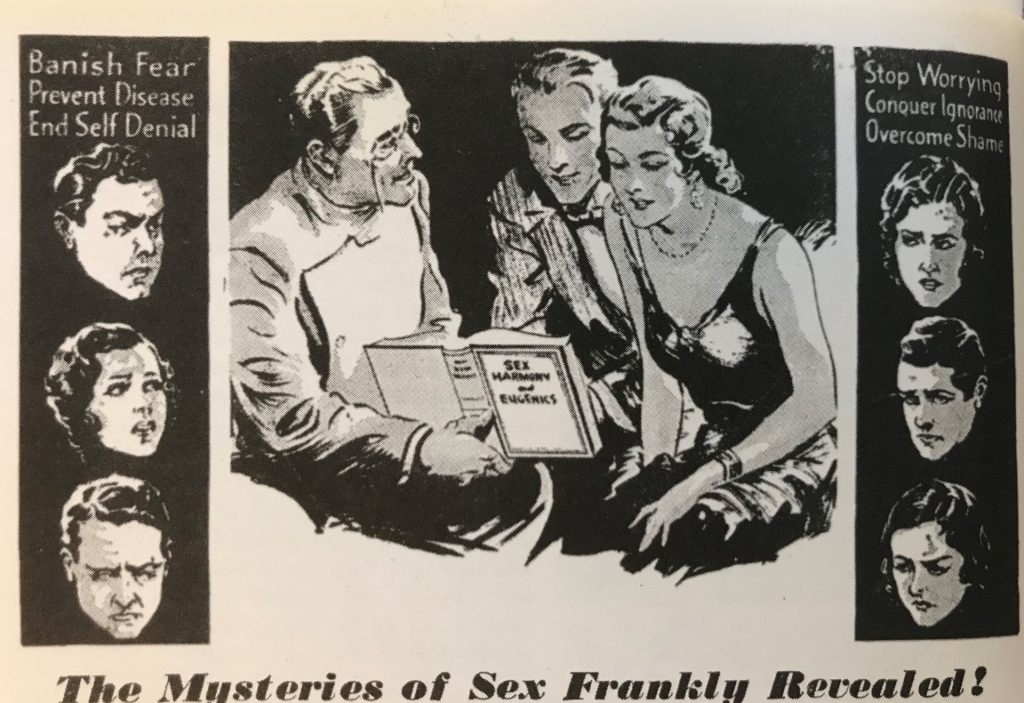

In it, I look at how advice texts in the early twentieth century discussed sexual difference, and specifically the idea that men and women had specific, and very different, roles to play in the marital bedroom. I essentially show that during a period of great upheaval and anxiety, advice authors argued that notions of sexually passive women and sexually active men were biologically mandated – even if they didn’t provide much proof for those claims, or make use of much scientific evidence at all.

In doing so, they cobbled together material to try and show that heterosexual marriage was right, natural, somewhat inevitable, and that anyone who strayed away from this was abnormal or even pathological.

Long story short, it is about how apparently ‘scientific’ ideas were marshalled to uphold a particular, quite conservative sexual status quo during a moment of real social change. This all speaks to my broader interest in ‘popular’ sexual science – I’m slowly putting a book together called The Science of Sex Advice: Popular Sexology in Print.

How did you become interested in histories of sexual science?

I’ve been interested in the relationship between sex, science, and print culture for a long time.

My PhD looked at how print culture facilitated sex radical networks in Britain and America, and particularly how ‘free lovers’ on both sides of the Atlantic used scientific ideas and rhetoric to challenge the idea that orthodox marriage was a good idea. After that I was a research fellow on a project called Rethinking Sexology at the University of Exeter, where I started working on popular sex advice and magazines. As part of that I spent a lot of time reading some of the brilliant new scholarship on sexual science, and also camping out in archives in both the US and UK to work through some amazing primary materials – stuff like sex advice pamphlets sold in vending machines and train station platforms for a couple of cents a go, slightly racy texts sold through mail order in the back of newspapers, and expensive manuals written by scientists and sexologists that were apparently only for the eyes of ‘professionals and academics.’ There’s such fantastic work being done on histories of sexual science, including some exciting new bits of scholarship on how the public engaged with science when making sense of their own sex lives. I hope my work can be part of those conversations

What is the importance of the history of sexuality today?

I think, for me, there’s so much to be said about how an engagement with science has shaped the way we think about sex. It might seem like a bit of a niche topic, but actually the way we talk and think about sex – even today – is absolutely replete with scientific ideas.

Why, for example, do we often use terms like ‘homosexual’ and ‘heterosexual’ (which emerged from nineteenth-century sexology) to categorize ourselves? Why are some people so obsessed with looking for a ‘gay gene’?

Why are we told that certain sexual behaviours and identities are good or bad for our health, or are perhaps ‘natural’ or ‘unnatural’? Part of my work speaks to these kinds of questions, thinking through how and why science has come to have so big a role in how we understand, discuss, and experience sexuality.

More broadly, I think that in a fraught social and political moment histories of gender and sexuality are more important than ever. I’ve been lucky enough to work with scholars trying to use history to find more helpful and inclusive ways to do sex education in schools, and to help young trans and non-binary people navigate the modern medical system. Historians in the field have been called on to shape policies around things like access to abortion, gay marriage, and how to tackle sexual violence. Doing histories of gender and sexuality helps us develop our understanding and appreciation of the past but, beyond that, engaging with that history also allows us to gain new insights into urgent and timely issues in the present.

What advice would you give to a student interested in the history of sexuality?

Be careful when opening some kinds of primary sources in public areas.

I was working on a train once and the person in the seat next to me threatened to have me arrested. It wasn’t even anything that bad, but that’s public transport for you.

What’s the best advice you ever got about history?

Someone once told me that it’s a gift to be able to indulge your curiosity, especially for a living. Not always a particularly accurate depiction of my job, to be fair, but I try and remember it when I’ve got a huge pile of reading to do.

What’s the most interesting thing you’ve read in the last twelve months?

That’s a tough one. History-wise, I really enjoyed Martha Robinson Rhodes’ article on Bisexuality, Multiple-Gender-Attraction, and Gay Liberation Politics in the 1970s, so probably that.

I’ve finally gotten around to starting Kate Lister’s A Curious History of Sex, too, which is really fun so far. I also read some good books this summer that were very much for pleasure, not work. Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi was mind-boggling (in a good way, I think) and I quite enjoyed Emily Danforth’s Plain Bad Heroines.

If you had a time machine, where and when would you most want to go?

My official answer to this is that I’d go back to have a raucous dinner party with some of the Victorian sex radicals I studied as part of my PhD. However, the truth is that I’d go back to 1997 and watch the Spice Girls at Wembley again.

What’s your must-do Bristol experience?

I’m pretty new to Bristol so don’t have many suggestions, but so far I’d recommend Pinkmans for donuts and Bakesmiths for cinnamon rolls. All the major food groups covered, what more do you need?

What are you working on next?

Loads of stuff!

I’m slowly making progress on the book, and I’m also working a new article on the concept of happiness and how this has been connected to ideas about good sex. I’m starting a new project which looks to encourage people to engage with queer history though playing games, and am also doing research into how we can help students transition from school to university.

Should keep me out of trouble for a little while, at least…