In the latest in this new series, we talk to Dr. Jiayi Tao about her doctorate, recently completed in the department.

Under the support of the China Scholarship Council, Jiayi Tao carried out her PhD project at the University of Bristol, passing her viva in September 2021. Her research interests lie in the history of international humanitarianism and modern Chinese history.

Hi Jiayi: first of all, congratulations on your successful viva! What was your doctoral research about?

My doctoral research focuses on the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA)’s operations in China (1943-1947).

It is a brief but crucial episode for us to understand the rise of non-western actors in the history of internationalism and that of humanitarianism. As the first executive organisation of the United Nations, UNRRA had a far-flung scope. It was aimed at solving various post-war problems through international cooperation.

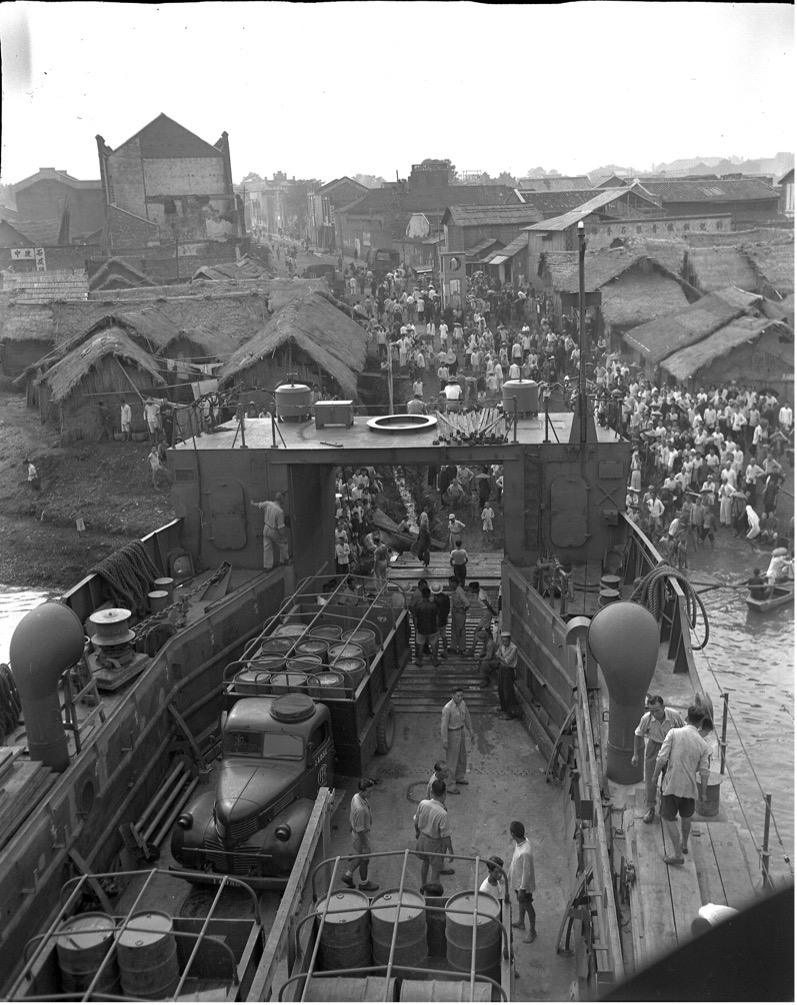

UNRRA trucks and gasoline being unloaded in Changsha, capital of China’s Henan province (UNA: S-0801-0011-0001-00007)

While historians have highlighted UNRRA’s role in dealing with Europe’s refugee crisis in the aftermath of the Second World War, we still know little about UNRRA’s cooperation with the Chinese Nationalist government, at a time when China was released from its one and only task of resisting Japan, a task that had lasted for eight years.

The distinctiveness of the case of UNRRA in China also lies in the fact that China emerged in the post-war era as a fully sovereign state, after the 1943 abrogation of the so-called ‘unequal treaties’ with imperial powers.

My thesis not only explores the ambition and capability of Chinese nationalists to utilise international aid, but also shows the response of Chinese civil society to changing Sino-foreign relations and the experience of foreigners who worked for China’s post-war relief and rehabilitation undertakings.

How did you become interested in the history of UNRRA in China?

I was initially interested in the history of post-war China. My Masters dissertation looks at the staff reorganisation and post-war rehabilitation of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service in the mid-1940s.

This research led me to the topics of rising nationalism and anti-foreign, notably anti-American, sentiment in post-war China. Just before 1945, the United States was still China’s most powerful and reliable ally and enjoyed reputation among Chinese public. I want to understand this rapid change in Sino-foreign relations on the ground, and I find that the scholarship of modern Chinese history has been almost exclusively focused on the Chinese Civil War (1946-1949).

I then shifted my focus to the UNRRA China Programme and sought to situate this case study in a broader scholarship of international humanitarianism.

Let’s talk about the viva itself. What would you advise someone who is preparing for their own viva?

I would say: don’t have prepared answers or try to guess what the examiners will ask, as some viva questions will always be unexpected.

But I think it is useful to try to conclude your key argument and key conceptual contribution. This is a step back to look at your thesis thoroughly, not just as an author but also as a reader. There are other tips that can help build your confidence, such as reading your examiners’ work and being familiar with your own thesis.

I would quote my supervisor’s words of encouragement for anyone who is preparing for viva: you have worked on this research for years and read more widely in this field than anyone else… including your examiners. So, whatever your examiners ask, you will have something to say!

Lastly, keep in mind that viva is a constructive process!

What’s next for you, Jiayi?

I will soon start a post-doctoral programme in the Shanghai Jiao Tong University. It is a new but exciting challenge. And I am working on developing a chapter of my thesis into a journal article, as well as developing a book proposal.

We look forward to seeing this work out in the wild! Thanks for talking to us today!