Will Pooley is Lecturer in Modern European History. His research explores popular cultures, folklore, and witchcraft in modern France. He is particularly interested in creative historical practices, such as history through games, theatre, poetry, art, and creative writing.

What’s your new book Body and Tradition in Nineteenth-century France about?

The book is about trying to understand what it felt like to be an ordinary agricultural worker or artisan in nineteenth-century France. What were the bodily experiences, and how did ordinary people use their own bodies?

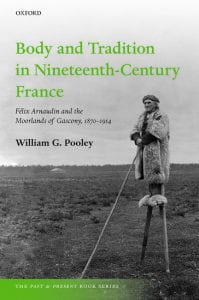

To answer those questions, I used this huge ethnographic archive collected by the folklorist Félix Arnaudin in a small area around his hometown, between about 1870 and 1914.

To answer those questions, I used this huge ethnographic archive collected by the folklorist Félix Arnaudin in a small area around his hometown, between about 1870 and 1914.

Arnaudin’s an interesting man in some ways, but what really interested me was the people he collected folklore from and photographed. I wanted to understand their stories, songs, and proverbs. So, I use the tools of comparative folklore to explore they talked about sex, work, and body parts.

What do werewolf stories, for instance, tell historians about how the rural population thought about identity and transgression? How does analyzing dialect speech help us to understand a bodily culture that was quite different from our own?

How did you become interested in Arnaudin and French folklore more generally?

I owe the interest in folklore to David Hopkin, who first suggested folklore as a research topic to me when I was a master’s student. I did a master’s thesis on one storyteller and singer from the Massif Central, an illiterate woman named Nannette Lévesque.

For my PhD, I wanted to do something much more ambitious. I was going to compare three folklorists from southwestern France – Arnaudin, along with Jean-François Bladé, and an interesting folklorist named Antonin Perbosc, who had very unconventional politics, and collected a lot of obscene folklore. But when I was about 14 months into the PhD, I knew I would only have time to do Arnaudin’s work justice… so that’s how I ended up with the subject of this book.

For my PhD, I wanted to do something much more ambitious. I was going to compare three folklorists from southwestern France – Arnaudin, along with Jean-François Bladé, and an interesting folklorist named Antonin Perbosc, who had very unconventional politics, and collected a lot of obscene folklore. But when I was about 14 months into the PhD, I knew I would only have time to do Arnaudin’s work justice… so that’s how I ended up with the subject of this book.

What is the importance of this research today?

Everyone has a body: it’s the definition of being human. And one of the things about embodiment is that our own experience and expectations of the body can seem deeply ‘natural’ to us. The ways we use and talk about our bodies become automatic, invisible.

I’ve always thought that one of the things history can do is to challenge that seeming naturalness. Even our very recent ancestors felt differently in their skin. They described and understood their bodies differently. They had different expectations and fears of their flesh.

How different I am from a shepherd born in 1815 might not seem a burning issue, but I think that part of the value that history has for the wider society is that it highlights some of these differences, and makes them visible. It’s a reminder that what we experience as ‘normal’ for our bodies now is not necessarily what other people around us are experiencing. And that’s a message that some people need to hear more than others, because their unspoken assumptions are normalized and taken for granted in all sorts of ways in everyday life.

If bodies were different in the past, they can also be different now, and they will be different in the future. That’s the message I have always taken from work by scholars like Barbara Duden, Lyndal Roper, Annmarie Mol, and even Michel Foucault.

What advice would you give to a student interested in the history of the body?

There’s so much exciting work being done in the intersecting fields concerned with bodies in the past. I was always fascinated by the new work on anthropometrics, for instance, even though I never did any of that kind of research. Anthropometricians like Deb Oxley and Jane Humphries have used historical and archaeological records of body sizes and weights to investigate questions such as the effect that the Industrial Revolution had on the health of workers, or the ways that families divided limited resources when they did not have enough to eat…

But my advice for someone interested in the history of the body would be two things. First, get to grips with the philosophical and theoretical work on the body. When I started this project ten years ago, I found Lisa Blackman’s short introduction The Body pointed me in the direction of lots of useful things.

The other thing I think I would advise anyone who wants to be a historian of the body is to use practice as research. Cooking historical recipes, trying historical clothing, even imitating movements, gestures, and work can be a really important way of grappling with the difference of the past.

What’s the best advice you ever got about history?

‘You’ve got enough.’

I have a running conversation with one of my colleagues at Bristol, Julio Decker, about not overdoing research. I’ve been working on a database of material collected from historical newspapers for the last six years, and I have too much material. But [in the time before COVID19] every few days, I [would] say to Julio, ‘I really want to go and visit this archive to find a few more cases’, or ‘I just need to spend a few hours nailing some of these details down in some online newspaper records’.

And Julio says to me, ‘Stop it. You’ve got enough.’

That’s great advice. There’s such a temptation to just keep collecting and hoarding material.

What’s the most interesting thing you’ve read in the last twelve months?

I really loved David Shields’ Reality Hunger, which was a present from a colleague, the playwright Poppy Corbett, who has been working with me on my latest project.

It’s a provocative book made up of lots of little short sections, organized into broadly thematic chapters. There are no quotation marks or footnotes, but the afterword explains that some of the material is actually taken from other writers. The book is about this hunger for reality that has dominated lots of cultural forms for the last generation or so – from memoir, to documentary, reality TV, and hip-hop.

I think it has a lot to say to historians about history as part of the same cultural impulse, a desire to ‘tell it like it really is’ but to do so in a way that is artful and compelling.

If you had a time machine, where and when would you most want to go?

This is a tough one! I don’t think I would really much enjoy visiting many of the people I research. I’m not sure we would even be able to understand one another: I taught myself to read the Gascon dialect Arnaudin recorded folklore in, but I can’t speak it!

I’d be quite interested to attend a nineteenth-century criminal trial in France, though. I’m working on criminal trials at the moment, and sometimes the newspaper reports give vivid impressions of courtroom dramas. Sometimes you want to know more. It would be fascinating – as well as probably quite distressing – to sit in on one of those cases, and see how they played out.

What’s your must-do Bristol experience/activity?

Chilli Daddy’s is a Szechuan restaurant with a few branches, and a stall at St Nicholas’ Market.

If you haven’t tried it, you should definitely have the soup noodle first. They offer it in a spice rating of 1-5. I’ve never tried higher than 3!

What are you working on next?

The newspaper database and court cases are research from my current project on crimes of witchcraft in France from 1790-1940. It’s a big topic, and I’m halfway through an Arts and Humanities Research Council grant to work on ‘creative histories’ based on this material. You can read some of the things we’ve been up to here: https://creativewitchcraft.wordpress.com