In this series, Dr Jessica Moody, unit co-ordinator of the third year Practice-Based Dissertation option, interviews students about their projects and experiences of this unit. The Practice-Based Dissertation was first introduced at Bristol in 2020-21 and enables students to produce a practical, public-facing ‘public history’ output as well as a 5000 word Critical Reflective Report.

In this interview, Jessica talks to Kim Singh-Sall about her project.

JM: Let’s start from the beginning, what made you choose the Practice-Based Dissertation over the standard Dissertation?

KS: When we did the History in Public project briefs last year, I found that I really enjoyed doing public history and wanted to take up the opportunity of creating a project instead of coming up with just a brief. Creative ways of telling history are not only fun, but also gives you the opportunity to approach history from a much more personal angle, which I wanted to explore in my dissertation. We do so many essays, so I thought taking the practice-based dissertation would make me feel more inspired about my dissertation!

JM: Could you tell us about your public history project?

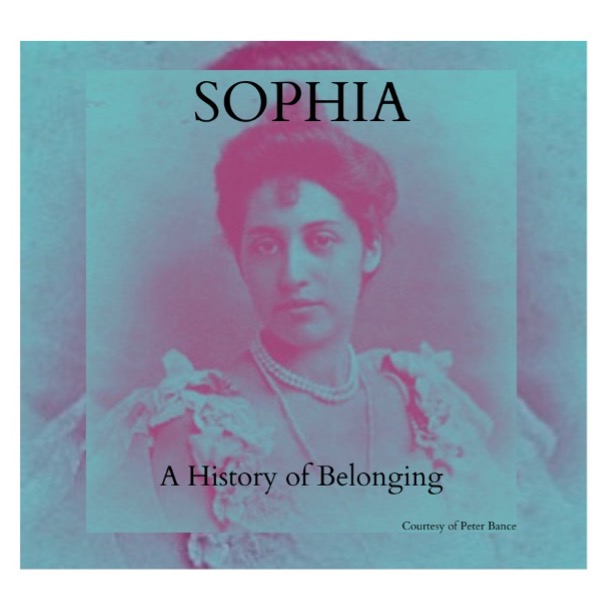

KS: I created a short podcast series about the life and legacy of Sophia Duleep Singh. She was the youngest daughter of the last Maharaja of the Sikh Empire, but was born and brought up in England and was Queen Victoria’s goddaughter. She was an English socialite and became a Suffragette. I wanted to tell her story, as she is a largely unknown figure in both British and Suffragette history, but also because she was a British-Punjabi woman, like me. My approach was therefore very personal, as I framed the podcast around identity, specifically relating to nationality and ethnicity. I drew on Sophia’s and my own experiences to help tell the wider story of what it means to be part of two worlds and balance two identities. I supported my podcast with an Instagram account where I posted episode recaps, recommendations for further readings, and photographs.

JM: Why did you want to undertake this project?

KS: This project felt very personal to me. I came across Sophia was I was about 15 or 16 and it was the first time I really saw myself in history, so it feels full circle to do my dissertation on her. I also want more people to know about her, especially British-Indians, because it is so important that people get to see themselves in history.

Image shows a portrait of Sophia Duleep Singh, with her name ‘Sophia’ and the subtitle ‘A History of Belonging’

JM: What did you enjoy most about the Practice-Based Dissertation?

KS: I enjoyed how creative I could be: from writing the scripts, to designing the Instagram posts, to finding the musical interludes in the podcast. It really allowed me to tap into different skill-sets and create something I’ve never done before. I also really enjoyed that it was public facing, because my drive behind the dissertation was wanting more people to know about Sophia, so it felt really great to have people listen and learn about her, possibly feeling some of the things I felt when I first came across her.

JM: What did you find challenging?

KS: I found writing the scripts to be a challenge, because I had to ensure I was being informative, while personal, writing in a way that would lend itself to people listening, rather than reading. I also found recording my audio quite challenging because I definitely over-thought my ‘podcast voice’ and had never edited audio before so it was a lot of trial and error. I’m not very good at navigating technology, so that was a big challenge!

JM: Did you come across any problems that you needed to address or solve?

KS: My main problem was something I discovered once I’d created the output when I was collecting feedback as I found that no one over the age of 60 had listened. That could mean both a technology and language barrier. I was targeting British-Indians, and definitely relied on my family and family connections to get listeners, but most of the first-generation British-Punjabis don’t speak native English and may have found it difficult to listen to the series.

JM: What do you feel you’ve learnt from this process?

KS: Beyond the technical aspects of writing, recording, and editing a podcast, I’ve learned how to make telling history accessible and engaging to an audience who might otherwise not engage with history. The process has spurred me to want to do similar projects in the future as I’ve seen how creative and gratifying it can be to put something out into the world.

JM: What do you think public history needs more of? Do you have any reflections or advice from your project for public historians?

KS: I would say that public history needs more personality and emotions. My project was very personal, and I think it made for a stronger historical communication and engagement with my audience. Not only is it cathartic for historians, but I think it is more interesting for audiences too. Sometimes we might think infusing our historical research or outputs with our own personal reflections, anecdotes, or stories might seem to be overstep, but I think now more than ever that’s what people are looking for. Public history is a great medium to make people feel seen in history, and adopting a personal approach is an effective way to do so.

JM: What advice do you have for students just starting the Practice-Based Dissertation?

KS: Trust the process! The prospect of creating something and putting it out into the world might seem daunting, but it’s a process and isn’t as scary as it seems. I’d say it’s important to have confidence and conviction in yourself – that what you’re creating deserves to be shared. Also, take advantage of the incredibly cool opportunity you have to do literally whatever you want about whatever topic you want. Be creative and have fun with it! On a more practical level, I’d recommend doing a lot of the public history readings for your report in the first term, as well as researching your actual historical content, so in the second term you can really focus on your output before doing your report.

JM: How can people find out more about your project?

KS: You can find the podcast on Spotify and follow the Instagram!