In the third of our posts for Disability History Month, Lena Ferriday writes about the novelist Dinah Craik.

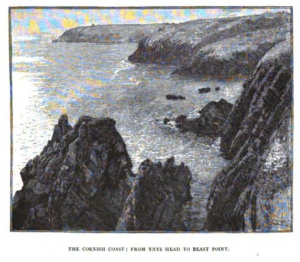

In 1881, at the age of fifty-five and six years before her death, novelist Dinah Craik took a sixteen-day excursion around the Cornish coastline. Craik’s reflections on this experience, recorded in a published travel journal, bring to attention a range of narratives regarding differently abled bodies which converged at the nineteenth-century coast, which became seen as a space which emphasised a linear pathway from illness to health, which differently abled bodies did not conform to. This post highlights the way in which discourses of different abilities have historically relied on the fit, or misfit, between body and environment.

Dinah Maria Mulock Craik, ‘An Unsentimental Journey Through Cornwall’ (London: Macmillan and Co, 1884) p. 15.

Nineteenth-century medical discourse attested to the coast as a therapeutic space. Physicians often prescribed visits to Cornwall for a ‘change of air’, expecting that the cold, strong, fresh winds would arrest the patients’ bodies from the state of ‘melancholy’ with which they had been diagnosed. For Craik, indeed, the Cornish coast was a corporeally nourishing space. ‘The air so fresh and pure, yet soft and balmy’, she recalled ‘it felt to tender lungs like the difference between milk and cream. To breathe became a pleasure instead of a pain.’ Concurrently, however, discourses of adventure culture considered coastal landscapes an ideal place for testing the corporeal capabilities of bodies, the difficulty of navigating them integral to their appeal.

In neither discourse, however, did the differently abled aging body cohere with the landscape. It could not be ‘cured’ by the coastal air, nor its capabilities attested to by navigation across the the cliffs. Indeed, Craik wrote extensively of the continual reminders of her body’s limitations posed by the landscape of the coast, which caused her discomfort and pain. For her younger travelling companions, ‘the picturesque or romantic always ranked second to the fun of a scramble’ as the ‘descent to this marine paradise […] seemed difficult enough to charm’ them. In comparison Craik was incapable to move across the cliffs, and even as she sat watching the others ‘scrambling into the most inaccessible places’ she was physically ‘uncomfortable’, negotiating her feet with ‘the long grass to prevent slipping down the slope’.

Whilst Craik was not socially marginalised by way of her body’s abilities, her reflections highlight the extent to which discourses of medicine, health and recreation constructed the coast as a space only physically able or healing bodies could cohere with, and from which the differently abled were excluded.