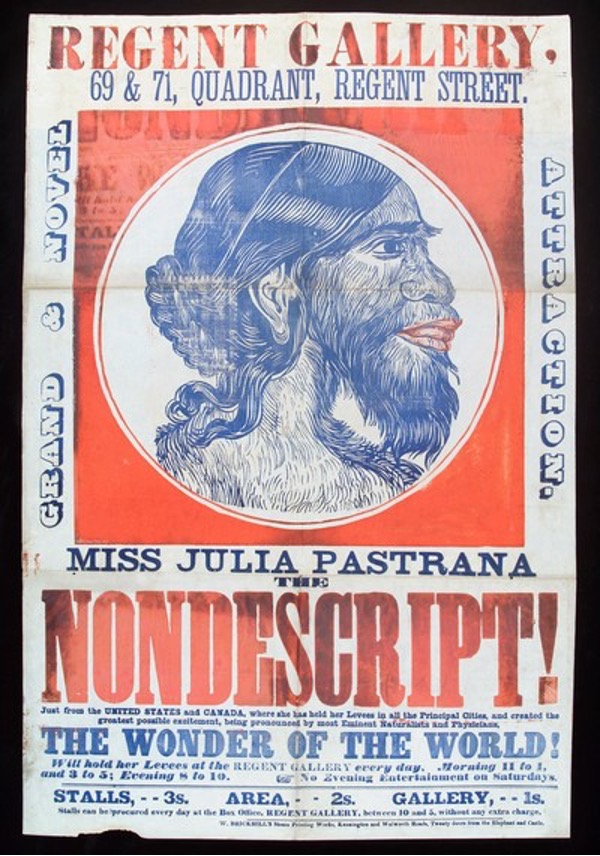

In the first of our snapshot posts for Disability History Month 2021, Dr. Andy Flack discusses the life of Julia Pastrana.

Julia Pastrana, a First Nations Mexican woman, was born in 1834. She died only twenty-five years later, having lived with a genetic condition known as hypertrichosis terminalis and which, in conjunction with other medical conditions, manifested as a series of physical characteristics – including the hyper production of hair and the swelling of lips and gums – which thoroughly inscribed her body with a gendered, racialized, and speciesist Otherness. This triad of perceptual lenses intersected in transformative ways. In popular discourse, Pastrana was thoroughly ‘freaked’, becoming known as the ‘Bear Woman’, the ‘Ape Woman’, or simply the ‘Nondescript’, and displayed across Europe and North America in the ultimate theatre of stigmatic staring: Even in afterlife, her body was embalmed, ‘freakish’ deviance captured to satiate the probing curiosities of mid-nineteenth-century scientific communities.

Pastrana was one among countless people – think Joseph Merrick, Stephen Bibrwoski – whose physical appearance rendered them objects of fascination and, not infrequently, disgust. Leading Disability Studies scholar Lennard J. Davis argues that ‘we live in a world of norms’ and that these ‘norms’ are cultural constructs with histories that need to be excavated. The modern ‘freakshow’ is perhaps the ultimate manifestation of an idea of what it meant to be ‘normal’ – to have a ‘normal body’ – at any particular point in time. And in Pastrana’s afflicted body, we find multiple and intersecting deviations from the supposedly standard types of the Victorian age. In her case, transgressions of gender norms (body hair) combined with culturally and historically contingent ideas of femininity and racialized physical stereotypes to position her as something not-quite-human. At the same time, her unavoidable humanity, captured in the movement of her body and the sound of her voice, meant that she could not be understood as not human (animal) either. ‘Bear woman’, ‘Ape Woman’, ‘Nondescript’; these terms meant that she could be seen as both, a liminal being whose apparently animal inferiority made her eminently exploitable. A commercialized vision of life at the margins. ‘Freakshows’ were alien worlds for the Normals.

Pastrana’s life resonates for people living with disabilities today, for the freakshow is not behind us. The token disabled person, who is thrust forward to speak on behalf of physical deviance, is still a spectacular attraction for the Normals. Public spaces often remain sites of penetrative staring, and animalized disabled lives are formed, figured, and ended at the intersections of gendered, racialized – and many other – experiences and stereotypes.